Born in Vicenza to a Venetian family in 1602/1603, Pietro Della Vecchia studied painting in Venice between 1619 and 1621 under Carlo Saraceni and Jean Le Clerc.

From 1622 to 1626, he lived in Rome, where he came into contact with the Caravaggisti and, above all, with the French artistic community. There he met Nicolas Régnier—painter, art dealer, and his future father-in-law—as well as the so-called Candlelight Master (1579–1650).

After returning to Venice around 1635, Della Vecchia likely worked for a period in the workshop of Padovanino, who influenced his interest in sixteenth-century art.

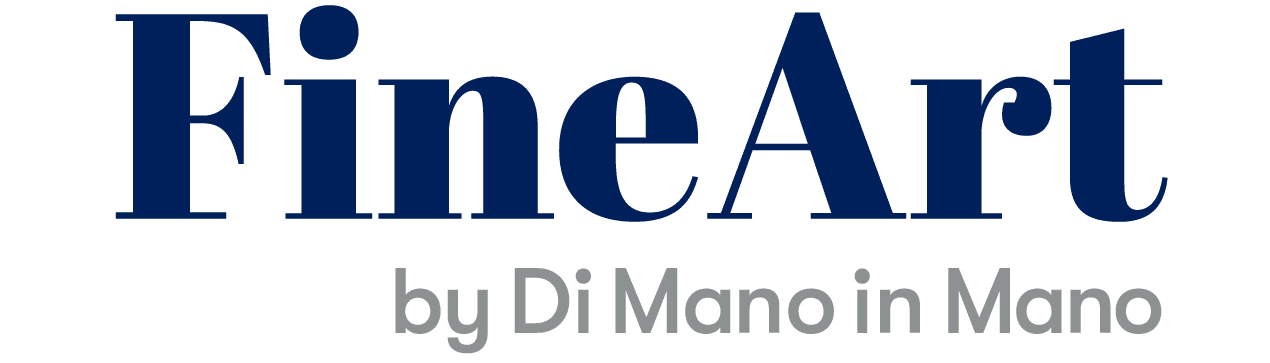

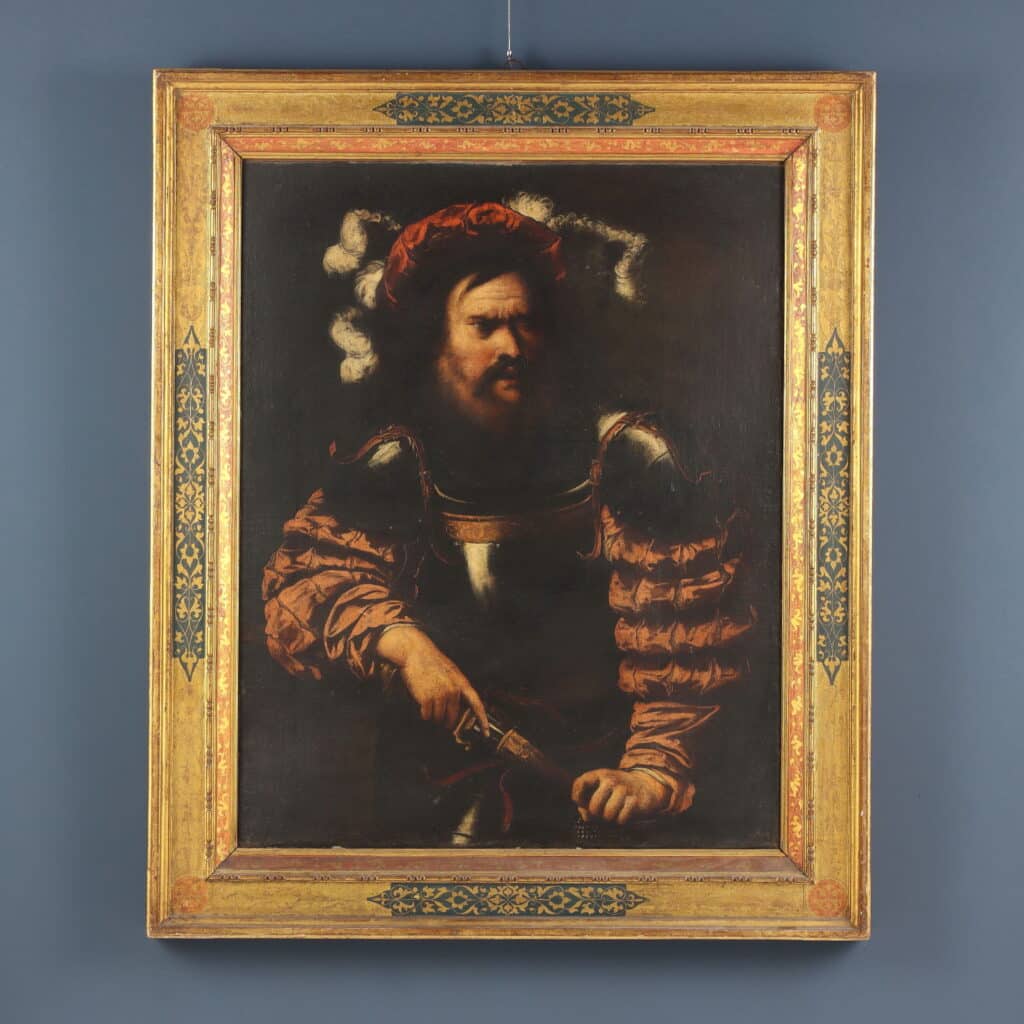

It was from this period onward that Della Vecchia and his workshop began producing a vast number of works in the style of Renaissance masters—especially Venetian ones. He painted an endless series of compositions inspired by artists such as Giorgione, Titian, Romanino, Palma Vecchio, and Bassano. These were not mere copies but ingenious reinterpretations admired in the seventeenth century as demonstrations of virtuosity and intellectual homage to the past.

His extraordinary ability to reproduce the style of sixteenth-century Venetian masters earned him, from his contemporary Marco Boschini, the nickname “Simia Zorzon” (the “ape of Giorgione”). Yet Boschini himself observed: “These imitations are not copies, but abstractions of his intellect, made to capture Giorgione’s manner.” (Boschini, 1660).

Some scholars even suggest that the surname Della Vecchia (“of the old”) may have been an artistic pseudonym, chosen to emphasize his attachment to the models of the great Venetian painters of the Cinquecento rather than a true family name.

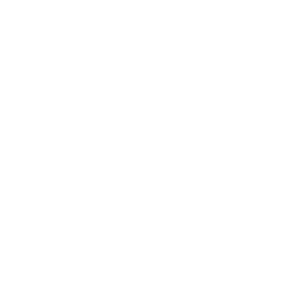

At the same time, the artist also produced works reflecting the modern sensibility of his own century. The 1640s and 1650s marked an especially productive phase in his career, spanning a wide variety of genres—from cartoons for the mosaics of St. Mark’s Basilica (as official painter of the Republic of Venice, he designed the mosaic cartoons between 1640 and 1673) to religious scenes, portraits, allegories, historical subjects, and the celebrated heads and brawls. These latter works not only imitated Giorgione’s hand but also his themes, often depicting male figures in sixteenth-century dress or soldiers with plumed helmets and gleaming armor.

Della Vecchia became particularly known for his paintings of soldiers—known as bravi—wearing large feathered hats. He produced numerous variations on these subjects, both as individual portraits and in genre scenes. The popularity of these compositions, however, led to many replicas by his workshop, which negatively affected his posthumous reputation.

From about 1650 onward, his work shows a renewed Caravaggesque influence, evolving toward greater dramatic intensity. This culminated in his series of canvases (originally seven, of which only two survive—The Conversion of Francis Borgia and Marco Gussoni in the Lazaretto of Ferrara) painted for the cloister of the Jesuit church in Venice between 1664 and 1674. These works, marked by macabre themes, spectral lighting, and a claustrophobic spatial compression, remain unique within seventeenth-century Venetian painting.

In his later years, Della Vecchia returned to producing more conventional religious paintings, inspired by earlier masters, as well as more luminous historical scenes.

During the 1640s and 1650s, he also maintained close ties with the libertine circles of the Accademia degli Incogniti in Venice, creating works that reflected the mathematical, philosophical, and cabalistic ideas cultivated in that milieu—sometimes treating them with seriousness, other times mocking them with satirical or risqué imagery.

Pietro Della Vecchia died in Venice in 1678.