A nativity scene from eight hundred years ago

Representations of the Nativity can be found as early as the 3rd century, often featuring the Virgin and Child dyad or the Holy Family, placed inside a stable or cave and sometimes accompanied by shepherds or the Magi. But these representations are purely pictorial or in bas-relief in precious materials such as ivory, such as the 10th century example from Constantinople and now preserved in the Louvre Museum in Paris.

The nativity scene in its modern sense, i.e. as a plastic representation of the birth of Jesus, was born only later, in medieval times, thanks to Saint Francis. In fact, this year marks the eight hundredth anniversary of the first choral representation of the Nativity: on Christmas night 1223 the “poor man of Assisi” set up the first living nativity scene in the town of Greccio.

The famous episode is told in the Legenda Maior, a biography of the saint written in Latin by Bonaventura di Bagnoregio, which reports “How blessed Francis, in memory of the birth of Christ, ordered the nativity scene to be prepared, the hay to be brought, that the ox and the ass were led; and he preached on the nativity of the poor King; and, while the holy man held his prayer, a knight saw the Baby Jesus in place of the one that the saint had brought.”.

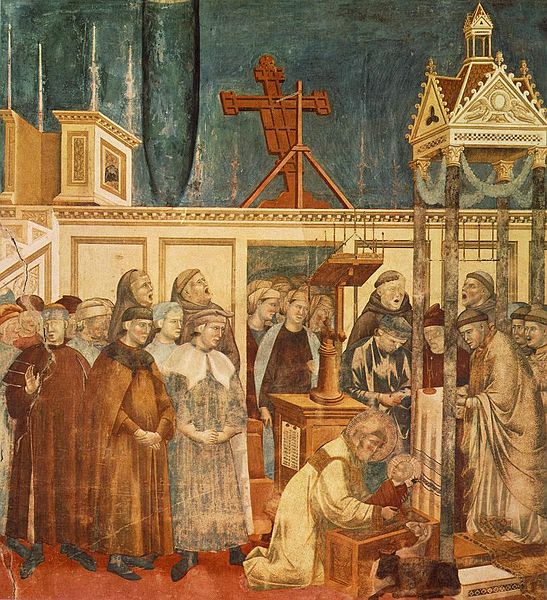

Precisely this miraculous event linked to the sacred staging was one of those selected for the Stories of Saint Francis, created by Giotto in the Upper Basilica dedicated to the saint, in Assisi.

The idea of a living nativity scene began to mature in Italy’s patron saint as Christmas approached that year to celebrate the birth of Jesus, but also to experience firsthand the harsh conditions in which it had occurred. The choice of the hills of Greccio was obvious, as he was linked to these hills which reminded him of Palestine and Bethlehem, and being close to the lord of these places, Giovanni Velita, involved him directly in the preparation of the event.

From this first representation, the success of the Nativity in art had a real increase: much requested by both religious and secular clients, the greatest artists of the Renaissance saw at least one work on this theme in their catalogue. Just to mention some of the best known ones, the Mystical Nativity by Sandro Botticelli, the evocative unfinished Adoration of the Magi by Leonardo, or even the Adoration of the Allendale Shepherds by Giorgione, immersed in a characteristic natural landscape.

Starting from the end of the 13th century, in the wake of the living nativity scene of Greccio, all-round sculptural representations of the Nativity became established, often interpreted with that chorality that added a strong empathetic component to the scene. One of the first was Arnolfo di Cambio, with his marble nativity scene created for the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome. Not only stone, but also wood was one of the favorite materials, one of the oldest is that, painted in polychrome, created by an anonymous sculptor for the Bolognese Basilica dedicated to Santo Stefano. Both statue groups could also be correctly titled as Adoration of the Magi, there being the Holy Family (in the Roman version also accompanied by the ox and the donkey) and the three kings with the gifts.

But when talking about nativity scenes, the Neapolitan tradition cannot fail to come to mind, which is still so famous and sought after today. The first exhibition with life-size sculptures dates back to the 1470s, today in the Neapolitan Charterhouse of San Martino. The real turning point for the Neapolitan nativity scene occurred in the Baroque era and again during the eighteenth century. The scenes became crowded, with great attention to theatrical and scenographic performance; particular care is also taken in the choice of characters, often belonging to everyday life: shepherds, artisans, members of the upper classes, offer a cross-section of contemporary activities and social figures. They also began to change the manufacturing techniques, using not only wood, but also glass for the eyes, wire and fabrics for the clothes.

Perhaps the most characteristic of the known ones is the Bourbon nativity scene of the Royal Palace of Caserta: the figures are placed on the so-called cork “rock”, re-proposing what was the last display of 1845, created on the occasion of the inauguration of the Naples railway -Caserta.

The nativity scene is a representation that has its roots in Italian tradition, but which is still much appreciated today, re-presented during the Christmas period, but always sought after by collectors.