French art glass from the end of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th century

According to an ancient legend handed down to us by Pliny the Elder (Naturalis Historia), the invention of glass took place in Syria on the sandy banks of the Belus river, by Phoenician nitre merchants who, busy tinkering with fire in a camp, they created the new material purely by chance. Although this story does not seem to be confirmed by archaeological evidence, which dates the first use of glassy material (decorative glass paste) to the 3rd millennium BC. in the Mesopotamian area, it refers us to an almost mythical dimension of the creative act, understandable given the high degree of production difficulty that made glass very rare at least until the 1st century BC, when the blowing technique was introduced.

Although we believe a more detailed analysis of the history of glass in the various eras is essential, here we will focus only on one of the fundamental stages, corresponding to the birth of artistic glass as we conceive it now, characterized by new forms and processing methods, in clear departure from the stylistic models turned to the past which until then had characterized European artistic glassmaking production.

This need for innovation, which has its roots in the mid-19th century, was born in response to the poor level of quality introduced on the market with industrial production, first denounced by John Ruskin on the occasion of the International Exhibition in London in 1851, and fought in second half of the century by the newborn movements for the revival and valorization of decorative arts and craftsmanship, first of all Art & Craft in Great Britain.

If we were to define the genesis of art glass with a single phrase, I think this could reasonably be “going back to the past without looking at the past”, where the first past symbolizes the high degree of technical expertise achieved by the art and crafts in the pre-industrial period, an increasingly rare commodity at the time, while the second represents, as mentioned above, a stylistic repertoire now crystallized in canonical forms and typologies linked to a taste that looks to the ancient.

This socio-cultural context led to the birth of Art Nouveau (also known as floral or Liberty style), a new style that first introduced the concepts of design and architecture in its contemporary meaning.

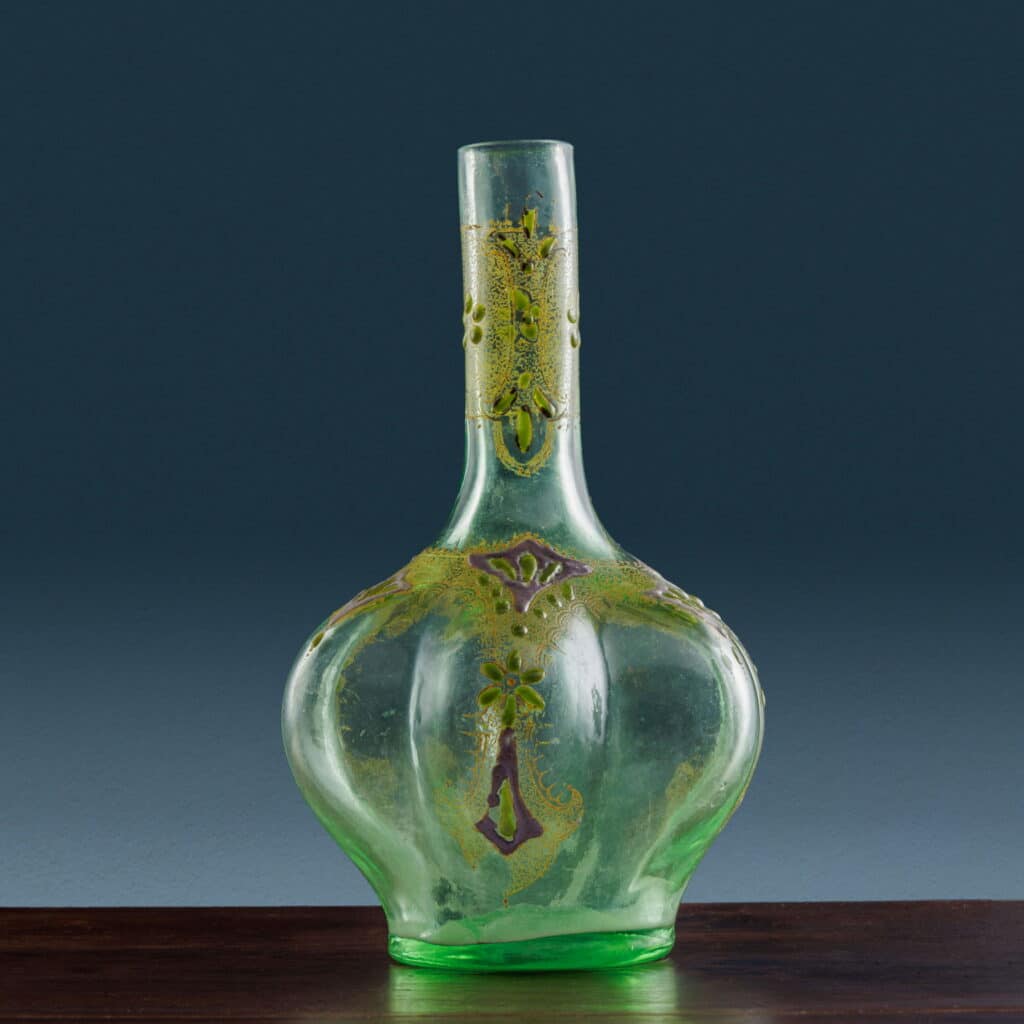

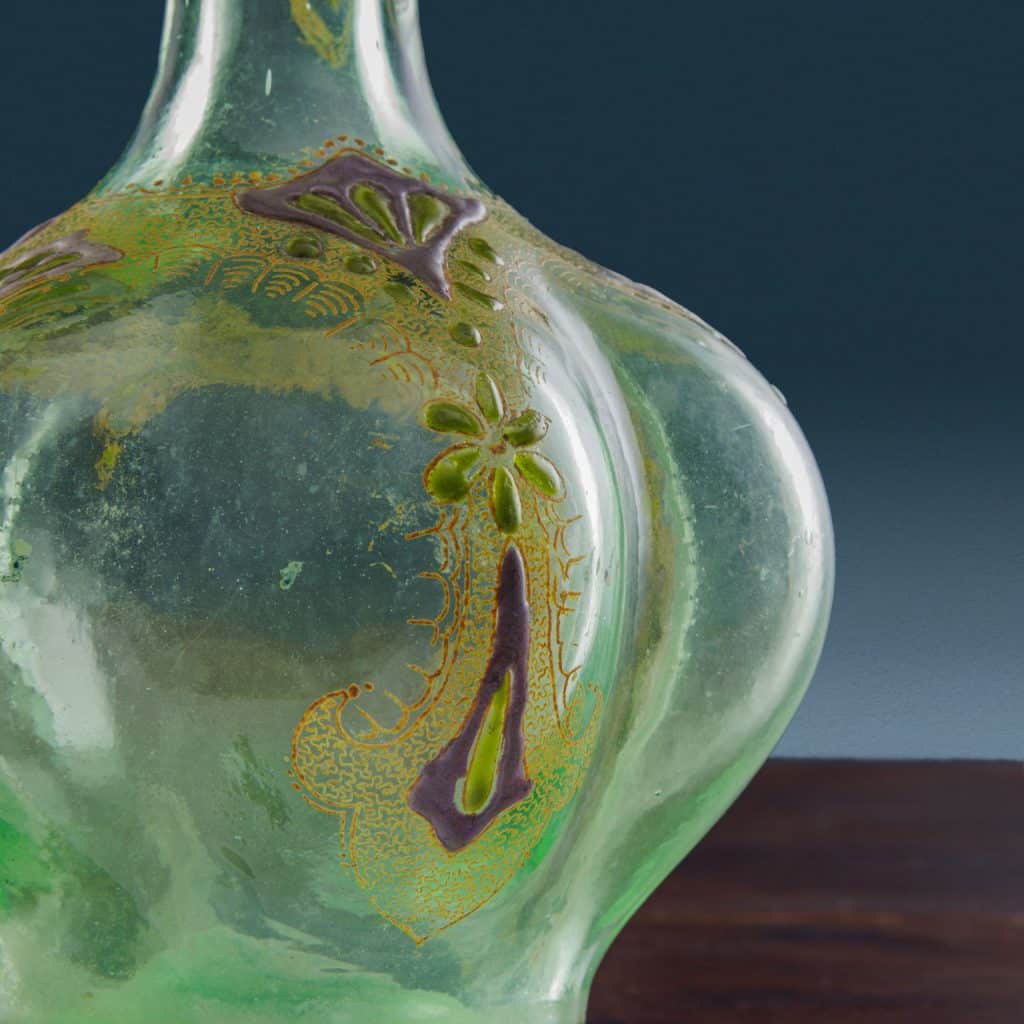

It was France and in particular the city of Nancy, a center located in the Grand Est region, that gave birth to one of the globally recognized personalities among the founders and leading exponents of French artistic glass manufacturing, pioneer of the new movement. Émile Gallé (Nancy 1846 – 1904) laid the foundations for the development of his unique style as a child, growing up surrounded by the decorative arts and traveling throughout Europe as a boy, in search of new techniques and inspirations. In 1877 he took over from his father in the family factory after an initial period of approach and experimentation with enamelled glass: this allowed him to try his hand at the first creations defined as “Transparent”, characterized by blown glass decorated with translucent enamels.

Strong were his passions for nature (botany and mineralogy) and philosophy, which were promptly reflected in his works until the late 1880s, first with the production of “Opaque” glass, among which we remember the effects imitating marble, agate and other semiprecious stones, and subsequently with the “verres parlant”, decorated with engravings with verses and stanzas of famous poets both contemporary and of the past, among which we mention Baudelaire, Paul Verlaine, Dante Alighieri and Shakespeare.

Another of his major interests was that of oriental art and iconographic and stylistic motifs inspired by Japan, a passion developed at a young age and which reached maturity at the end of the 19th century, in line with the strong influence that the East had in this period on Western art. In Gallé’s production this influence was forcefully manifested not only in the decorative apparatus, but also in the vascular shapes and signatures, the latter with a setting and clear references to Japanese calligraphy.

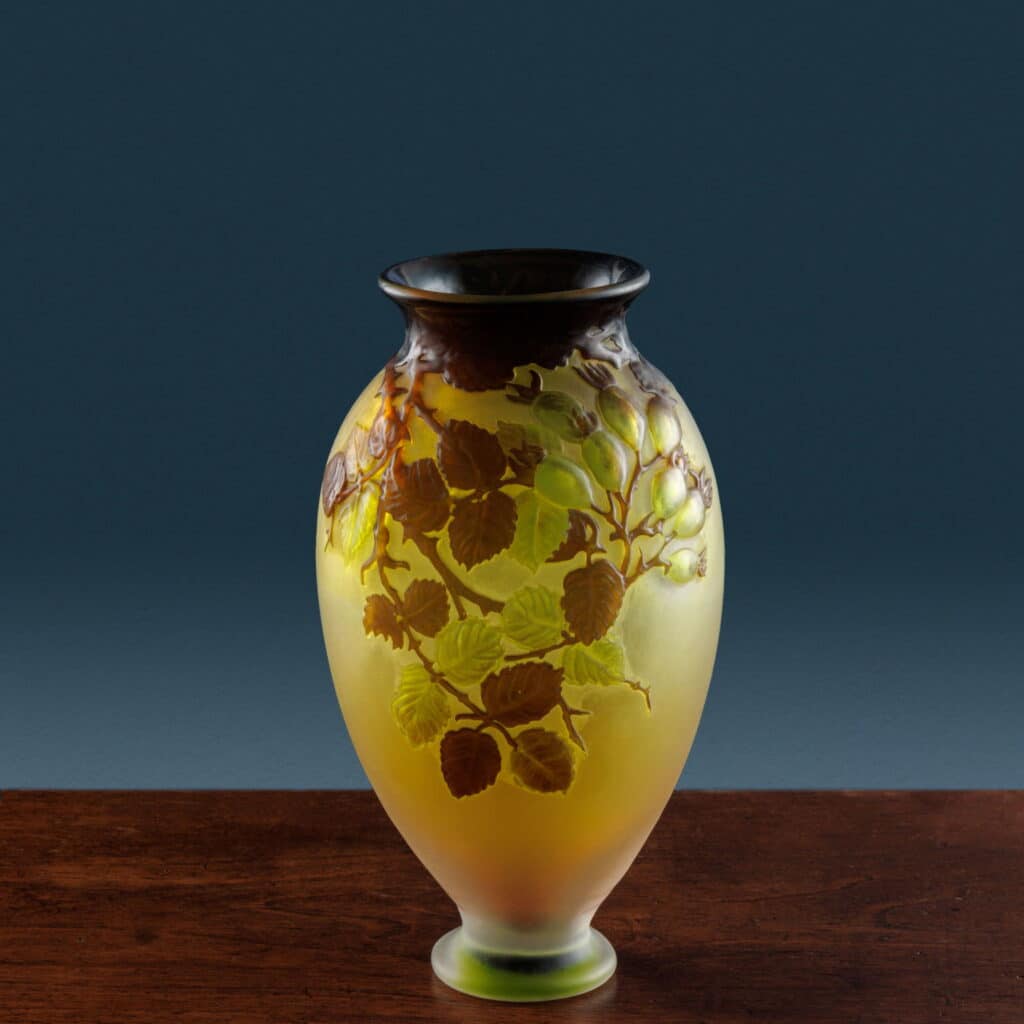

But what most marked Émile’s production was introduced starting in the 1990s, we are talking about “cameo” glass, so-called for its resemblance to the cameos produced by the processing of shells, bone and semi-precious stones since ancient times. Examples of “cameo” glass are actually found as early as the Roman imperial age, but the great innovation that Gallé brought was the industrialization of the process thanks to the use of the hydrofluoric acid etching technique. This technique was used for the majority of Gallé’s production, both for the stylistic rendering and the expertise which allowed the great artistic value of the works to be kept unaltered, and because the production of glass in series allowed the processing times to be drastically reduced, making thus his art accessible to an ever-growing audience.

Finally, the “marqueterie-sur-verre” technique deserves special mention, a sort of hot inlay of glass of different colours, which represents a very limited production carried out in the last years of the nineteenth century, due to the high cost and great difficulty of the technique.

Gallé production continued even after his death (1904), until the definitive closure of the plant by decision of its last director and son-in-law, Paul Perdrizet, which took place in 1936. From this moment on, throughout the 20th century, it was there is a large quantity of fakes on the market which, although often made with a good degree of virtuosity, differ from the originals due to their inferior quality and some inconsistencies linked to the decorative motifs or the signature, which are not always easy to identify.

However, Émile Gallé was not the only brilliant artist of the Art Nouveau movement based in Nancy. In fact, during the last years of the 19th century, the first exhibitions of decorative and industrial arts of Lorraine began in which the artists of Nancy presented their works collectively, demonstrating a unity of purpose that reached its peak with the establishment, in February 1901, of the École de Nancy, a consortium created to promote the cultural-artistic influence of the city and the entire region, enhancing industries and crafts, creating a school and consequently a museum and related exhibitions. The association, directed by Gallé, brought together personalities of the caliber of Louis Majorelle and artistic glassmakers such as the Daum brothers, the latter heirs to the leadership in the French decorated glass sector after 1904.

Auguste and Antonin Daum gave the company started by their father in 1878 an artistic twist, bringing it to success and taking care of its growth throughout the Art Nouveau period. Antonin (1864-1930), head of the artistic direction of the family company since 1891, was the main architect of this success both from an aesthetic point of view and from the point of view of experimentation and technical innovation.

In fact, in addition to the splendid chromatic results obtained with the acid etching technique on glass with multiple layers of colour, a process already seen in use in the Gallé glassworks, the Daum manufacture is remembered for having patented the “intercalaire” decoration in 1899, consisting of covering the already worked vase with a layer of more or less transparent glass, in order to create nuanced “pictorial” tones and give a three-dimensional perspective effect. Another of the most original processes of the Daum glassworks is that of “glass powders”, which as the name suggests involved the inclusion of powders obtained from crushed colored glass inside a layer of transparent glass, arranging them according to one’s tastes until to obtain the desired effect.

Not to be forgotten are the works created with glass applications such as handles, cabochons and ornamental motifs in naturalistic forms, including insects of various kinds, or the “caged vase” created in 1920 in collaboration with Louis Majorelle, so defined because of the iron frame and perfect synthesis of multi-level craftsmanship.

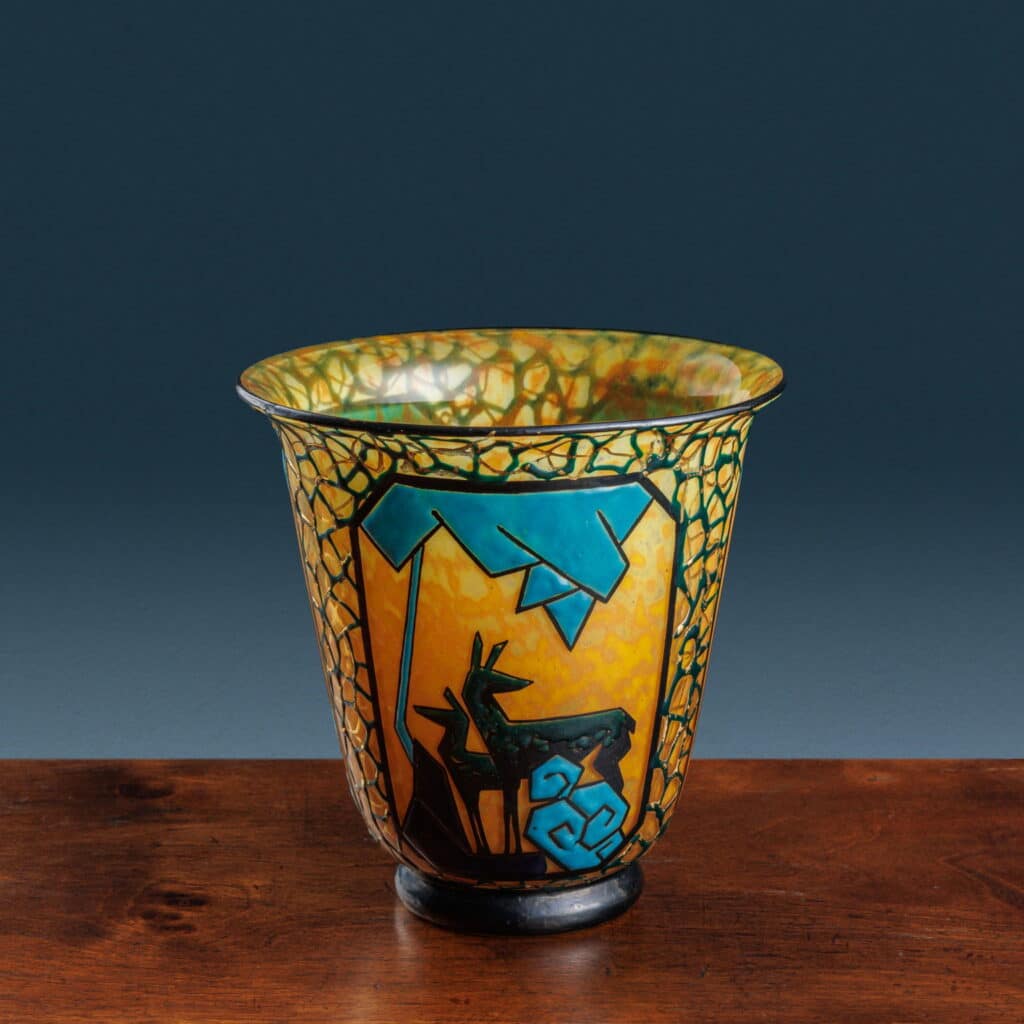

The Daum manufacture was able to evolve and align itself, in the 1920s, with the new stylistic current of Art Déco, although it was undoubtedly during the Liberty period that it managed to express itself with greater creativity.

The Schneider glass factory, started by the two brothers Charles and Ernest in 1913 in Epinay-sur-Seine, north of Paris, should be placed in the transition between Art Nouveau and Art Déco. It is curious that both trained as craftsmen in Nancy, working in the laboratories of the Daum glass factory. This manufacture is characterized by two production lines, belonging to two very distinct brands: the first, branded “Schneider”, embodies the creation of artisanal works in the true sense of the word, often in limited edition and characterized by bright and contrasting colours. obtained thanks to the “intercalary” or “marqueterie-sur-verre” techniques, while the second, branded “Le Verre Français” and “Charder”, includes industrial production including, for example, vases worked with the engraving technique acid. The Schneider glassware was able to align itself well with the now mature floral taste and at the same time exploit the emerging opportunities arising from the ongoing change, so much so that throughout the 1920s it managed to perfectly represent the Deco taste through stylized decorations (plant and animal world) and original geometries, showing a clear cubist influence. Its strong point was undoubtedly the innovative chromaticism, characterized by both a wide quantitative and qualitative choice, through lively and original shades: one above all the famous “tango” color, a red-orange of exceptional shine and liveliness.

Finally, last but not least, we introduce the figure who on a stylistic level differs most from the productions just analysed: René Jules Lalique (Aÿ-Champagne 1860 – Paris 1945), renowned jeweler and master glassmaker who trained between Paris and London before opening , in 1885, his own atelier in the Parisian municipality.

Active in the same socio-cultural context as his predecessors, René focused on the absolute originality of the designs he personally designed and on the very high quality and attention paid to the manufacturing process, initially applied purely in the goldsmith field, creating avant-garde jewels both in shapes and materials, so much so that he earned the epithet of “inventor of modern jewelry” according to Émile Gallé. Starting from the beginning of the twentieth century he began to seriously direct his creativity into the field of glass, continuing his goldsmith work, producing elegant objects in rock crystal and glass and starting to wink more and more at the commercial dimension, through collaborations with important perfumeries: the bottles from anonymous containers thus begin to take on autonomous artistic value and to provide added value both to the perfume contained and to the manufacturing company.

In 1913, following the purchase of a further glass factory, he managed to increase the production volume by diversifying processing techniques and manufactured articles, thus reducing costs thanks to the industrialization process. Among these we remember glass services that were exported all over the world and the original car radiator caps, introduced on the market during the 1920s.

On a stylistic level, the recurring themes in Lalique’s production, as well as sources of inspiration, were female figures, flora and fauna, undisputed protagonists of his creations of both Liberty and Art Deco taste.

At the conclusion of this summary overview of the fascinating world of French art glass between the end of the 19th and the first decades of the 20th century, which allowed us to introduce the main actors on the scene, we would like to mention an interesting exhibition currently underway (17 December 2023 – 21 January 2024) at the deconsecrated church of Santa Maria della Vittoria (Mantua, via Claudio Monteverdi 1).

“The magic of glass”, the title of the exhibition, is the result of a selection that took place within an important private collection of glass physically located in northern Italy and carried out with the aim of offering a cross-section of glassmaking art in France between Liberty and Déco, paying particular attention to the works created with the hydrofluoric acid engraving technique and to the production that I would dare to define as “submerged”, hidden from the view of the general public as it is often overshadowed by the great masters addressed in our article.

In fact, in addition to the works of Gallé, Daum, Schneider and Lalique, one comes across the production of artists considered by the most secondary (often erroneously) and that of “niche” or even unknown authors, which constitutes, according to Flavio Scilhanick, wise curator of the exhibition, “the true peculiarity – and therefore uniqueness – of the collection which is the subject of this exhibition”.

In perfect agreement with this statement, the visit allowed us to closely observe pieces of absolute value, characterized by different shapes, dimensions, colors and peculiarities, more or less rare, but all perfectly representative of the fertile socio-cultural environment that created them. products.

For all the reasons listed in this brief discussion and for their indisputable beauty, even after a century or more, these extraordinary glasses are still today a luxury good much appreciated and sought after by collectors all over the world.