The Art Nouveau Style

“Originality consists in returning to the origins.”

This quote by the famous Catalan architect Antoni Gaudí sums up the concept behind the artistic current that spread through Europe and the United States between the end of the 19th century and the first decade of the following century.

The precursor movement was in fact that of the ‘Arts and Crafts’, established in England in the second half of the 19th century and founded by John Ruskin and William Morris. The place of origin was certainly no coincidence: the mother nation of the industrial revolution and the increasingly massive production of what was defined as ‘applied art’ acted as the impetus for a deep change.

The massive production of furniture and furnishings, often in shoddy materials, led in fact to a deep reflection on both aesthetics and production methods, inextricably linked to a new awareness of the importance and reciprocal conditioning between art and society. Returning to the corporatism of medieval inspiration, however, this structure saw a rapid decline due to the very high production costs, which were unsustainable for the final consumer.

But by then the artistic revolution was underway and with Art Nouveau a sustainable result was sought.

The importance that this genre had can already be seen in the spread it had, taking on different nomenclatures in different nations, a symptom of the deep sense of belonging it carried.

Art Nouveau in France, Modern Style in Great Britain, Jugendstil in Germany, Arte Jóven in Spain, Sezessionstil in Austria, are all names that underline the newness of the new art, its break with the past.

The desire to make a break with the eclecticism prevailing at the end of the 19th century is in fact quite understandable: the revival of styles in vogue in the past had gradually turned into a mere and banal repetition of stylistic features, which increasingly offered redundant and ‘heavy’ furniture and objects.

If Neo-Renaissance, as well as Neo-Gothic and Neo-Baroque were born with the intentions of celebrating the great ancient models (and in high quality works the refinement is still appreciable), at a more mediocre level the result was now old, rather than ancient. This intolerance for late 19th century taste and the desire to look to new models was in fact already felt in Europe in the middle of the century even earlier in painting than in the applied arts: the Pre-Raphaelites in England, the painters of the Barbizon school at Fontainbleau forest, the Macchiaioli in Tuscany, were all united by a new approach to nature, its observation from life and the meticulous analysis of the events that define it.

It seems understandable, then, how at the end of the century, in an increasingly industrialised society, the arts continued to draw inspiration from nature, from its sinuous movements.

Significantly, this current is also often referred to names that suggest precisely the following formal elements: Lilienstil (lily style), Wellen-stil (wave style), Schnörkestil (spiral style), style coup de fouet (whiplash style); paling styl (eel style).

The light, airy movement is the basis of Art Nouveau, applied to furniture, jewellery and furnishings; one of the crafts that was most influenced by this current was undoubtedly that of glass.

It was in fact between the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, in France and in particular in Nancy, that two of the most important glassworks were born and established, which incorporated the aesthetic and other innovations of which Art Nouveau was the bearer: the Gallé glassworks and the glassworks run by the Daum brothers (see in-depth article on glass).

But this style also affected entire architectures and street furniture. Examples well known to the common imagination include the édicule Guimard, structures designed by the architect Hector Guimard as the entrance to certain stops on the Paris metro, precisely characterised by a formal analysis of the plant stem. Or, moving on to Spain, the parks and houses designed by Antoni Gaudì, colourful and with an almost dreamlike effect, a very personal version of Art Nouveau.

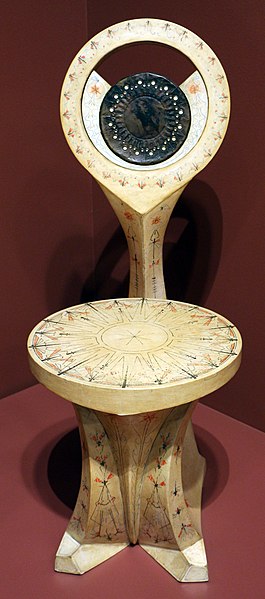

If in fact this style was the one adopted by fashion in those years, also thanks to the numerous national exhibitions, first and foremost the one in Paris in 1900, there were certainly some emerging personalities capable of adapting its stylistic features to their own very particular taste, such as the aforementioned Gaudì, the Scottish Charles Rennie Mackintosh or the Italian Carlo Bugatti.

Naturally, Art Nouveau also affected the art of painting. Just to mention the most famous and well-known Alphonse Mucha, Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele and, even earlier, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

As far as Italy is concerned, the matter deserves a few more small notes, starting with the Liberty nomenclature, derived from Arthur Lasenby Liberty’s London warehouses, focused in the sale of products from the East, a culture that generated a lot of attraction and often influenced the production of these years, the so-called Japonisme. The starting situation was different, that of a fledgling nation in which industrialisation was slow to set in, if not still embryonically in a few centres in the north of the peninsula.

Regionality and craftsmanship were still firmly rooted in the production of furniture, the return to a workshop dimension that was so much desired abroad was already taking place in Italy.

Even the relationship and comparison with the art of the past must start from different considerations: the revival of floral and phytomorphic motifs, the study of nature taken as a model from which creating new decorative forms was a practice already implemented in ancient times.

Since Roman times, the carved decorations on temple friezes and later on the walls of great halls, or the structural elements of furniture, are nothing but different interpretations of the leaf and flower motif. Renaissance grotesques, great Baroque volutes, Rococo rocaille and neoclassical phytomorphic symmetrical motifs are all different concepts, according to the taste of the time, starting from nature.

Here, then, is how Art Nouveau in Italy further connotes itself as a natural evolution, a variation on the same theme, now with an unavoidable focus on the functionality of the object itself, in a true precursor to modern design.