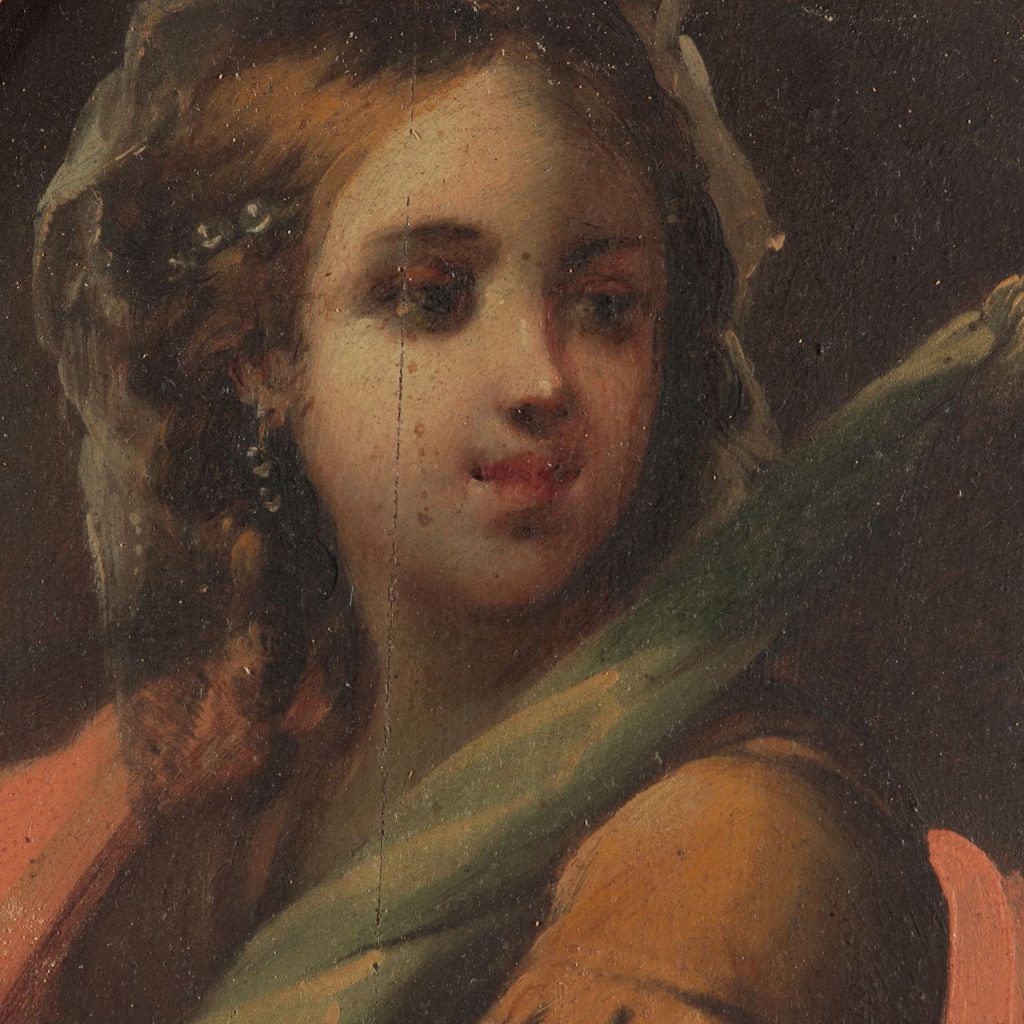

Francesco Conti (Florence, 1682-1760)

Heroines of antiquity, allegory of Night and Dawn

Painting Technique: Oil on octagonal white poplar

Description:

The group of eight paintings in question (figs. 1-8) represents, in the classic Florentine format of the octagon, a series of half-figure female effigies.

More precisely, they are elegantly dressed young girls, arranged in various attitudes but united, with the exception of two specimens on which we will dwell later, by the accent on wealth, highlighted both by details of sumptuous consoles and draperies, and by necklaces of pearls or precious fabrics that women sometimes handle, thus putting the accent on them.

One of the figures wears a royal crown on his head, others turbans or unusual headdresses. These details give the characters a princely aspect, sometimes combined with oriental references.

A formula that brings to mind the case of a painting recently rediscovered in its true identity, the “Portrait up to half-length of the Armenian Queen” by Mario Balassi, a seductive combination of Laurelian recoveries and elements of fantasy preserved in the Uffizi Galleries (see F. Berti, From Medici portrait by Jacopo Ligozzi to Queen of Armenia by Mario Balassi.

A historical-artistic case between critical fortune, documentary investigations and ‘Morellian’ observations in “Tactile Values”, 7, 2016, pp. 30-49). As mentioned, they are distinguished from the other two octagons, in which the girls occupy more space within the painting, appearing on a slightly different scale.

In one of these (fig. 1) the woman is recognizable with certainty in an Aurora, due to the star that shines above her head: “the great and shining star, which she has above her head, is called Lucifer, that is, the bearer of light” (C. Ripa, Iconologia, ed. Milan 1992, p.81).

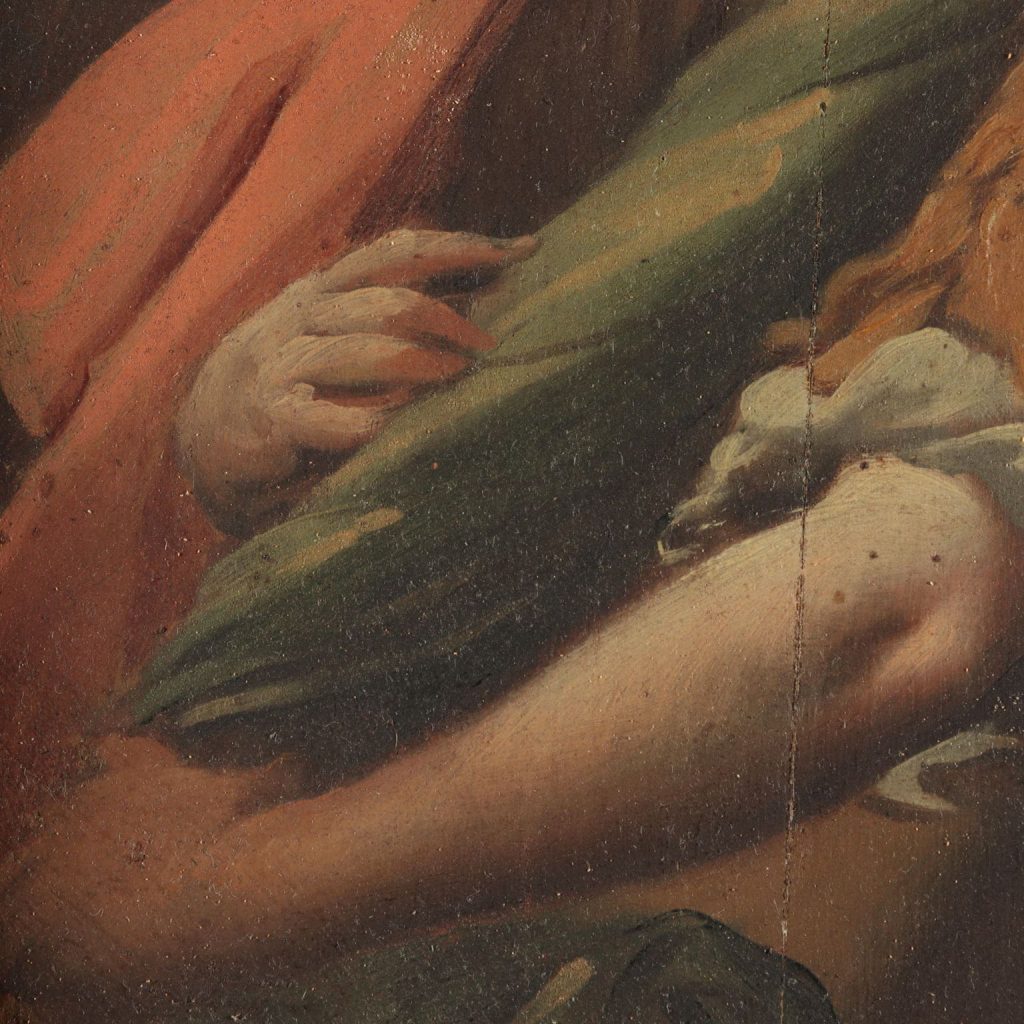

The other (fig. 2), of not so obvious identification, seems to us recognizable, thanks to the presence of her partner, in a Night: the young woman carries a large canvas wrapped around a rod, alluding with all probability – and an appreciable invention – to a customary attribute of allegory, namely a cloth that veils the light.

The plates, still preserved in their original gilded frames, are numbered on the back, in eighteenth-century handwriting, with numbers that are placed irregularly from number 4 to 23, certifying the belonging of this group of octagons to a larger series.

To confirm this hypothesis, one of the figures in the paintings in question, the one numbered with n. 23 (fig. 3), is known to us for another version (fig. 4), belonging to a series of four rectangular canvases by the same hand, also centered on female heroines, which appeared on the antiques market with an attribution to the painter eighteenth-century Neapolitan Jacopo Cestaro (fig. 5; 34.5 × 26.5 cm).

he three remaining figurations which do not match in our series were once to have appeared there, as were likely the other two parts of the day, Day and Twilight. The latter are traditionally entrusted to male characters, but we can imagine that the painter who performed them gave both female features.

This supposition is also suggested by the choices witnessed by a further series performed by the same artist, this time complete and centered on the Seasons. In this group of four oval plates spent on the antiques market (fig. 6; 28 × 22 cm) not only Spring and Summer are female, but also Autumn and Winter, periods traditionally symbolized by male protagonists.

The intriguing insistence on the female universe of these sets of paintings is also found in two additional octagons on a panel of almost identical sizes (fig. 7; 35.5 × 30 cm) and obviously by the same hand. These are the Allegory of Liberality and the Allegory of the Commedia from the Giovanni Pratesi collection, published as a work by the Florentine Francesco Conti (1682-1760) in the monograph on the artist (F. Berti, Francesco Conti, Florence, 2010, n.69 , pp. 214-215).

The stylistic identity of all the works mentioned is evident, always characterized by a fast and immediate workmanship, with rapid brushstrokes and a remarkable freshness of execution. It is therefore a hitherto unknown collateral activity to the production of large altarpieces and more demanding paintings, mostly of religious subjects, by the protege of the Riccardi family.

Due to the characteristics listed above, these creations find particular references in the author’s corpus, due to the similar expressive modality, anticlassical and almost unscrupulous in the abbreviated pictorial modes, in works such as the Blessing Christ and the San Sebastian (Berti, op.cit., n. 45, pp. 176-177) and in the group of paintings with scenes from the Passion (n. 46, p. 178). The realization of a series like the one in question, mostly depicting a set of queens and heroines of the past, finds antecedents in famous ensembles of paintings, always characterized by consistent numbers and similarly marked by the female universe, such as the review of beauties Romanes by Jacob Ferdinand Voet, created for the residence of Cardinal Flavio Chigi in Ariccia and then replicated for other Roman families, or, to stay in Tuscany, the series of the “Beauties of Artimino”, a parade of dozens of handsome Roman women and the court Medici painted at the end of the sixteenth century by various authors for Christina of Lorraine, or the sixty-six “Oval Beauties”, portraits of ladies of Lucca and Florence, made by Antonio Franchi around 1690 for Violante of Bavaria, wife of the Grand Prince Ferdinando.

Dimensions: 36 x 29 cm ( 14,7 x 11,41 in )

CODE: ARTPIT00001710

Biography Francesco Conti:

Introduced to the workshop of the famous painter Simone Pignoni thanks to the intercession of the Marquis Riccardi, at the beginning of the last decade of the seventeenth century, Francesco Conti was able to come into contact, on this occasion, with the art of other artists who collaborated in the management of the study and in the realization of the works commissioned to the now elderly master.

Among these, uncle Giovanni Camillo Ciabilli, elected Academic of Drawing in 1699, had to play a fundamental role in the training of the young painter, whose artistic language mediated Pignoni’s style.

A person of considerable intellectual caliber and personally attentive to the figurative arts, the Marquis Francesco Riccardi brought the eighteen-year-old Conti with him to Rome in November 1699, where he had the opportunity to see the greatest masterpieces of the city (in particular he came into contact with the art of Raphael and the Carraccis) and to participate in a real school chaired by Giovanni Maria Morandi and the famous Carlo Maratta.

In this period, fundamental for the formation of ours, is the study of drawing and ancient statues, together with an incessant practice of drawing from the natural, so much so that its presence is documented at the Accademia di San Luca and the Accademia of France.

It was in this context that he began his activity as a painter, especially with various cardinals and important Roman noble families, such as the Albans. In those years he also started his teaching career, initially as an art teacher for the daughter of the Marquis Cosimo Riccardi while from 1706 he will be engaged with the position of “Master of the Public School of Design”.

In 1705 he returned to Florence, in a city whose cultural landscape was vividly animated by the artistic choices of the Grand Prince Ferdinando, proponent of numerous commissions to artists: the Venetian Sebastiano and Marco Ricci, the Genoese Alessandro Magnasco and Antonio Francesco Peruzzini, the Emilian Giuseppe Maria Crespi, whose art brought innovative ideas to that of local authors.

Francesco Conti continued to be the painter of the Riccardi family, as indicated by the periodic payments of work materials and important commissions, such as a Pietà for the noble palace, noted in the registers and the three ceilings of the casino of Gualfonda.

The latter in particular are a clear expression of Conti’s painting, characterized by rigid and angular drapery, sparse and rather gloomy settings, well-rounded anatomies but not very rigid and uncoordinated. The juvenile phase is in fact characterized by the realization of paintings that present clear memories of another famous Florentine artist of the sixteenth century such as Andrea del Sarto, who certainly had to study in depth.

The second decade of the eighteenth century brings with it some stylistic innovations: greater serenity and abandonment of the severe Roman neo-sixteenth century accents in favor of a certain ease and chromatic serenity of a Venetian imprint: in 1715 it is the Adoration of the Magi for the Nuns of the Monastery Nuovo, a cornerstone work in the corpus of Francesco Conti, who definitively abandons the gloomy accents of the youthful period, softening the looks and faces of the characters and enriching the brushstroke, in imitation of the manner of Sebastiano Ricci. Tangencies with Venetian art can also be seen in the refined and material rendering of the clothes, in the lightness of the brushstroke and in the contrast between the orange light and the intense blue of the background.

An idealized standardization has now taken place in the faces, which assume the typical features used by Conti at this chronological height. During the fourth decade of the eighteenth century his greatest achievements saw the light, which earned him the decoration of the Spron d’oro, by Pope Clement XII. It is in these years that he creates important works that share a pictorial quality with remarkable technical and chromatic refinements.

These are paintings characterized by a precious chromatic range, very bright and contrasted, made to stand out by the light on the dark background or with ethereal effects, in line with the best European painting of those years. In this regard, we can remember the Saint Catherine of Alexandria in glory at the Civic Museum of Prato or the Return from the Flight into Egypt at the Cleveland Museum of Art.

- Heroines of antiquity, Francesco Conti, 18th century

Antiques, Art and Design

FineArt is the new ambitious Di Mano in Mano project that offers an exclusive choice of antiques and design works, presenting them for their singularity and uniqueness.