The neoclassical carvers of Savoy

The great and heterogeneous richness of Turin’s furnishings, paintings and furnishings is undoubtedly linked to the wealthy Savoy clients. Among the longest-lived and most important Italian families, the Savoy family was as active politically as it was culturally.

Moreover, it is now known how art and culture in general are historically used by the noble and powerful as a tool for self-representation, and therefore affirmation, of their dynastic pride. It follows that the main Italian and European courts contribute to huge commissions for their state buildings and residences, furnished in an opulent and sumptuous manner.

The rise of the Savoy family, and therefore the start of the main construction sites, began in the mid-17th century and continued until the mid-19th century, albeit with some interruptions due to the French, first at the end of the 17th century and then with the descent of Napoleon’s armies a century later.

These incursions led to the destruction of numerous nobility delights and to dispersions, partially stemmed in the years of the Restoration, when the dominion of the Savoy was restored.

The period of maximum splendor was between the two invasions: with the re-foundation of the state and the reborn Savoyard dynastic pride, the eighteenth century was characterized by a new artistic drive. Countless construction sites saw their start in the 18th century, initially with the genius of Filippo Juvarra, called from Sicily in 1714 and active in the Savoy capital for twenty years.

The architect’s creativity is particularly appreciable in the Stupinigi residence, where he was able to build from nothing, without the limits of pre-existing buildings. These were succeeded by Benedetto Alfieri, whose style was characterized by the prevailing baroque taste of clear French derivation.

Only from 1780 did Neoclassicism find space in the workshops of Turin furniture and furniture makers, opening up to the new prevailing European fashion, with a view to renewing the royal residences. The direction passed to two other great personalities: the First Royal Architect Giuseppe Battista Piacenza, often assisted by Carlo Randoni, and Leonardo Marini, costume designer at the Teatro Regio and later also interior designer and ornament designer, with the position of «ordinary designer of the chamber and the King’s cabinet.”

Under their direction, numerous artists and craftsmen were active, highly specialized in the various working techniques to create scenographic but refined furnishings.

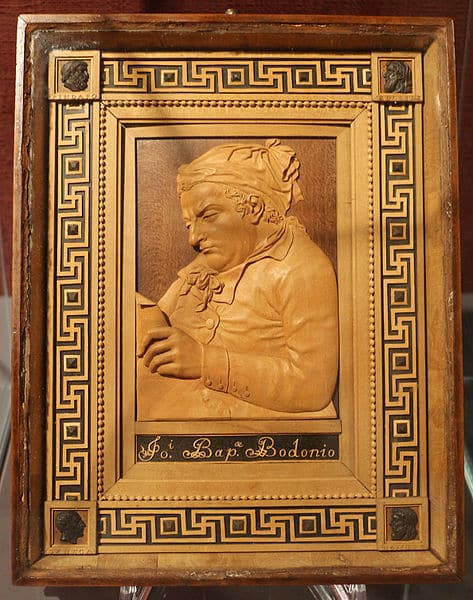

Among these, the name that stands out above all is certainly that of Giuseppe Maria Bonzanigo, a very refined carver who was able to be appreciated both by the Savoys and by the imperial authorities with the Napoleonic domination, and then returned to work for the Savoy house with the Restoration . His activity for the royal family is widely documented by archival documents and made known thanks to the work of Alessandro Baudi di Vesme thanks to the drafting of the records of the same name.

The first payment for “drawings, frame work, and various sculpture ornaments made in the current year” dates back to 1773, where our figure is active together with five other carvers.

His skill was such that the following year he was admitted to the Accademia di San Luca, until then intended only for “major” artists, i.e. painters and sculptors, while furniture artisans were sent back to the University (i.e. Corporation) of cabinet makers and cabinet makers.

This data is of a certain importance, not only because it testifies to the recognition of Bonzanigo’s activity by the artistic community, but also because it demonstrates how he mainly dedicated himself to the design and carving decoration of the furnishings, while the structural part was postponed to a minusiere (frequently Giovanni Gallinotto).

In 1787 he was appointed “wood sculptor” of Vittorio Amedeo III:

«La particolare abilità e perizia dimostrata dallo scultore in legno Giuseppe Maria Bonzanigo nell’eseguimento de’ diversi travagli statigli da parecchi anni a questa parte ordinati per nostro servizio, e di quelli singolarmente che ha in ultimo luogo con singolare maestria perfezionati, invitandoci a dargli un contrassegno della nostra beneficenza, ci siamo disposti a stabilirlo nostro scultore in legno, allo oggetto anche di maggiormente animarlo a distinguersi nell’arte suddetta […] coll’annuo stipendio di lire duecento».

Precisely in the mid-eighties Bonzanigo had worked in Stupinigi and these are probably precisely the jobs referred to in the royal nomination; at the end of the same decade he was active in the Apartments of the Duke of Aosta in Turin and at Venaria. The papers also give us an insight into how Giuseppe Maria Bonzanigo’s workshop, at this chronological height, must have already been well underway: from the census of the arts, thirteen collaborators appear to be present.

As is understandable, the royal supplies were interrupted in 1799 with the descent of the French troops but, as already mentioned, his great ability was to reconvert his art to create works appreciated by the new public.

Precisely in these years Bonzanigo began to produce expertly crafted microsculptures thanks to his ability as a fine carver.

These objects belong to one of the most well-known and sought after trends, in particular by the numerous tourists who in those years chose Italy as a destination for their travels and who purchased these curious objects as cultured souvenirs to bring back to their homeland. The production of micro-carvings also continued during the years of the Restoration, also thanks to the ever-increasing success of the Grand Tour, which saw the presence of a large number of foreigners passing through the archaeological ruins of Rome and southern Italy.

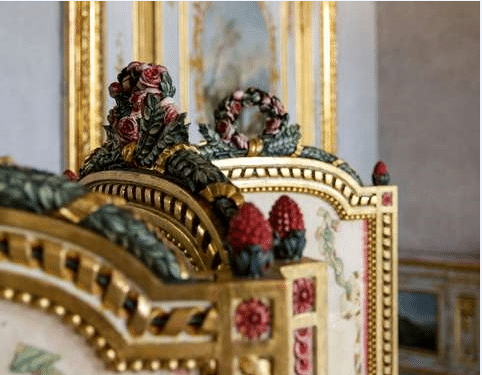

On the other hand, royal commissions also resumed, so much so that in 1820 Bonzanigo was involved in two construction sites for the royal residences: the Ballroom, called Rondo, in the Royal Palace for which he created four doors and as many carved trumeaux; subsequently in the castle of Govone, in particular in the king’s cabinets and in the queen’s bedroom.

His great skill in carving and above all his great inventiveness make Bonzanigo the most appreciated and well-known neoclassical carver of the Savoy family today. As already mentioned, although under the direction of personalities such as Piacenza and Marini, we are often responsible for the idea and design of the furniture then created. In fact, from his projects emerges the ability of an artist who, despite never having moved from Turin, was able to assimilate, making it his own, the most fashionable Italian and European figurative culture, free from provincialism.

If Bonzanigo figures as a prominent artist, he was not the only one to obtain the appointment of His Majesty’s wood sculptor. Even before him, Francesco Bolgiè had been appointed in 1775, to be joined four years later by Giuseppe Antonio Gianotti. The peculiarity of the second is that he was sent to Paris, to perfect his technique, only after his appointment and not before him, as would seem more logical.

During his career Bolgiè was widely appreciated by the House of Savoy, so much so that he was able to boast an increasingly higher salary than that of his two colleagues and was also recalled with the Restoration (among other things he was also active in the decoration of the new ballroom in the Royal Palace).

Its critical success, today as then, appears secondary compared to Bonzanigo. Frequently relegated to the background, if he appears to have licensed a greater number of furnishings for the royal family, the attribution of pieces made for other clients is more difficult.

Certamente a concorrere a questa difficoltà vi è il fatto che per lo più Bolgiè si avvaleva di disegni di Marini per la realizzazione dei mobili, non essendo egli stesso inventore. Inoltre, seppur attivo durante gli anni del dominio napoleonico, la sua capacità di riadattare la propria arte non fu pari a quella di Bonzanigo.

Continuing in his activity as a furniture manufacturer, he was unable, like his colleague, to understand the demand of the new clientele, specializing specifically in the creation of an object that found its own market specificity, such as the elegant micro-carvings highly requested by travellers.