A Grand Tour souvenir of 17th century Rome

In a curious booklet from 1828, Stendhal offers his friend Romain Colomb a series of useful advice in his capacity as an expert tourist in Italy at the time: “The cabmen on this route are more rogue than the others: when there are many English tourists they they also ask for 60 francs while the ordinary rate is 40 francs. It is not easy to find accommodation in Naples: look at the hotels in Santa Lucia, take a room on the fourth floor: you can see Vesuvius and the sea. Every evening, at 6, more than one boat leaves for Ischia, 10 pugs are requested; 3 or 5 at most are given.” In many respects, not much seems to have changed in the approach towards foreign tourists. At the time, Italy was the most popular destination for the legendary Grand Tour, a sort of initiatory journey, an indispensable training experience for young gentlemen from Northern Europe and immersion in the homeland of Art for artists and men of culture.

“A man who has not been to Italy will always be aware of his inferiority, for not having seen what a man should see”, this was stated by Samuel Johnson in the 18th century.

Italy has been a travel destination since the Middle Ages: the roads were then traveled by pilgrims heading to Rome.

But only during the 15th century did the vogue for secular and erudite travel begin which became a real fashion from the end of the 16th century. The term Grand Tour was coined by Richard Lassels in 1670 and configured what in the following century could be defined as a true annual European migration. The great archaeological discoveries of Herculaneum and Pompeii significantly increased the fame of the peninsula as an immense open-air museum of classical antiquity, as well as homeland of the Renaissance, of musical theater (how many pages of Stendhal’s Rome, Naples, Florence are dedicated to the prestigious Italian opera houses), of knowing how to live and of the sunny and mild climate.

The engine that moves groups of young people, writers and artists along the streets of Italy is curiosity and awareness of the educational value of encounters with the culture of the past. The pages of the countless diaries and reports of the Grand Tour report observations, meetings, reflections, intellectual experiences and unlikely episodes experienced in the streets and buildings of Italian cities: Rome, first of all, the most sought-after destination with its heritage of antiquity and history thousand years old, and then Florence, Venice, Naples, Milan, Genoa.

If the literature that gives an account of the journeys undertaken is endless, the resulting figurative production is equally endless: views, landscapes, monuments, reproductions of famous works, are produced as precious souvenirs of the Grand Tour, often by artists hired specifically in their homeland following the young gentleman, other times purchased by local painters, more or less famous: how many Canalettos adorn the halls of English castles and palaces, a memory of the journeys of distant ancestors? And how much does the nineteenth-century phenomenon of collecting owe to this fashion for landscape painting? Often it is the traveler himself who tries his hand: there have been many albums of pencil drawings or watercolors by talented amateurs who wanted to take home a more vivid memory of the places visited. The production of engravings, prints, etchings and topographical maps, especially of Rome, is endless.

Surely the young aristocrat or the artist studying antiquities who found themselves in Rome in the second half of the 17th century and wanted to purchase quality prints to bring back home as a reminder of the Eternal City could go with confidence to the shop on the corner via della Pace and via Tor Millina: the most important workshop for the production and trade of artistic prints in Rome was located here. The De Rossi family’s printing house “at Pace, on the canton, under the banner of Paris” had begun its activity at the beginning of the 17th century: Giuseppe De Rossi had moved to Rome from Milan and had established a solid business as a specialized printer in the reproduction of ancient monuments, a destination for passionate travelers on the Grand Tour. His son Giovanni Giacomo, who took over from his father around 1638, transformed a family-run shop into a truly internationally renowned workshop: from his presses, between 1638 and 1691, various plans of the city, archaeological maps and above all works dedicated to the representation of the ancient and modern monuments of the city were published.

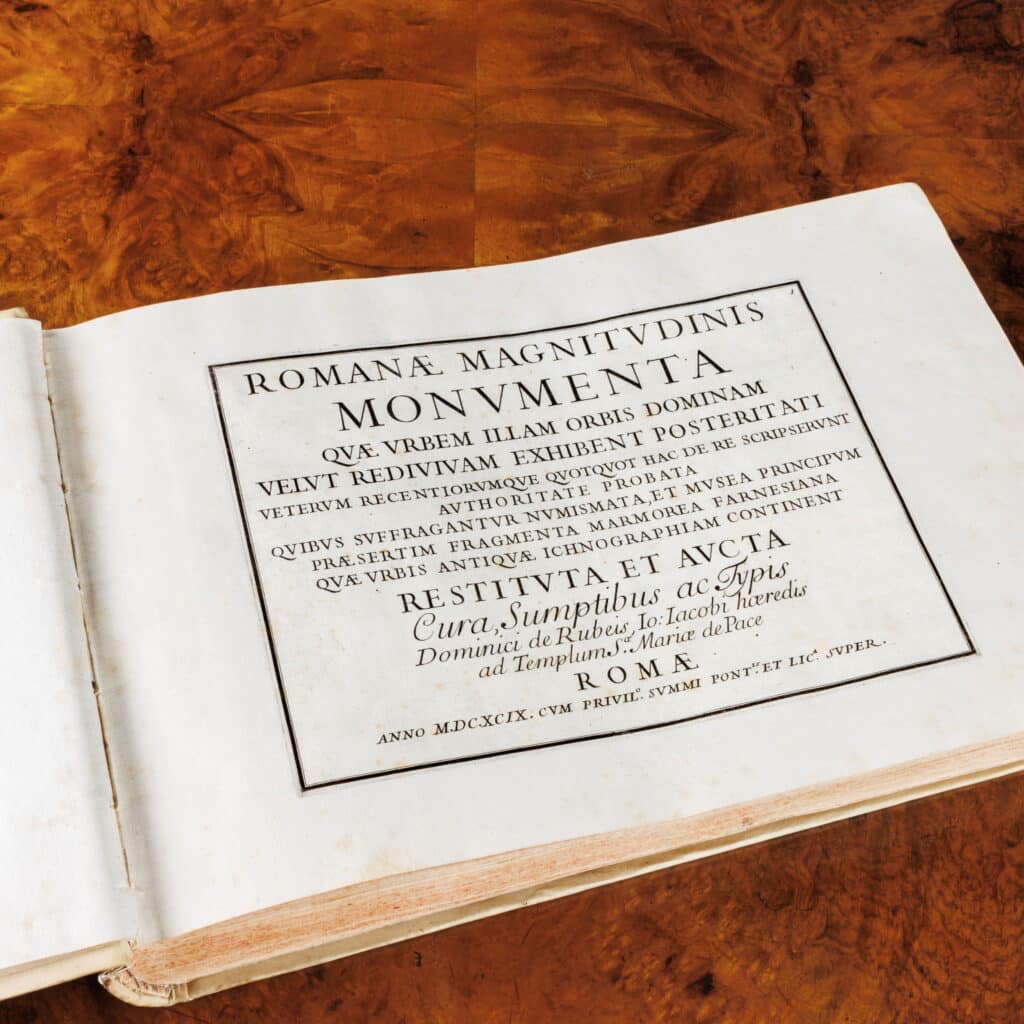

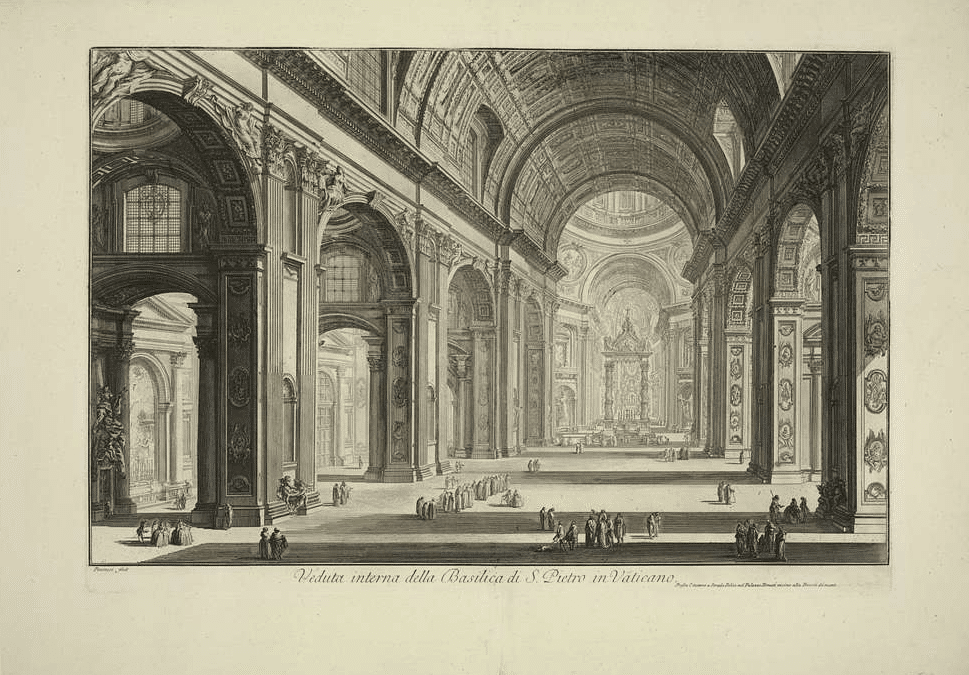

A beautiful contemporary parchment binding therefore brings together two truly fascinating works: the first, “Romanae magnitudinis monumenta quae urbem illam Orbis dominam velut redivivam exhibent posteritati”, was printed in 1699 Cura, Sumptibus ac typis Dominici de Rubeis, Io: Iacobi haeredis ad Templum S.Mariae de Pace. The aim of the volume is to re-propose in all their magnificence the buildings whose ruins filled the city of Rome. The collection of intaglio engravings opens with 18 tables of antiquarian interest on the history and customs of ancient Rome. These are followed by 118 plates, engraved and printed with clean and clear lines accompanied by accurate descriptions also carved in copper: all the most important monuments and archaeological sites of ancient Rome come back to life in their integrity for what the study of the archeology of era could reconstruct. The plates are not signed, but the Treccani Encyclopedia attributes this masterpiece to Pier Santi Bartoli, who is listed as an engraver at the bottom of the dedication plate of the work: “Bartoli’s reputation as an architect, or rather as an architectural scholar, is linked to the reconstruction proposed by him, in the act of engraving them in copper, of many of the most illustrious monuments of the City. Halfway between the sixteenth-century Speculum by A. Lafréry and the eighteenth-century Antiquities by G. B. Piranesi, Bartoli takes on his own, with a preparation and a disposition closer to the distinctly archaeological one of the former than to the essentially lyrical one and in a certain dramatic sense of the second, the theme of the “magnificence of Rome” and he dissects it with a tenacity and constancy that lasts an entire life, extending it to paintings, tomb lamps, to coins, to ancient gems”.

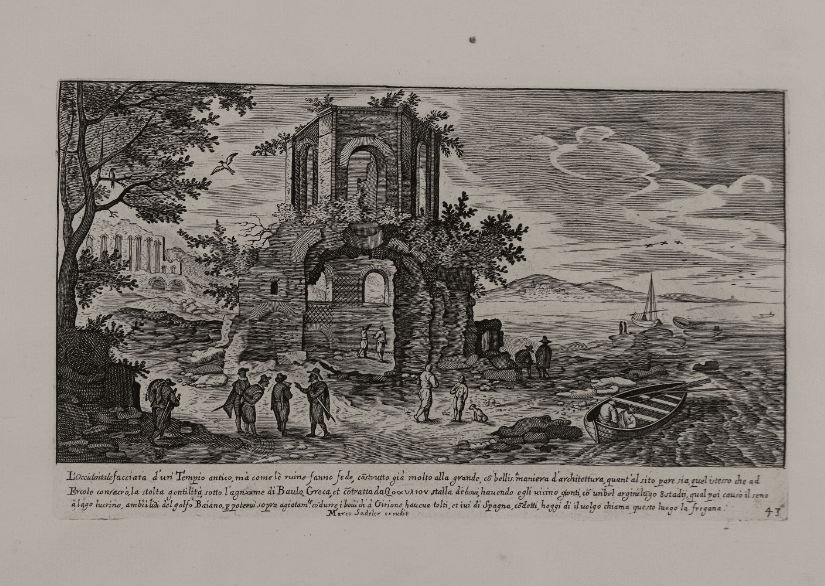

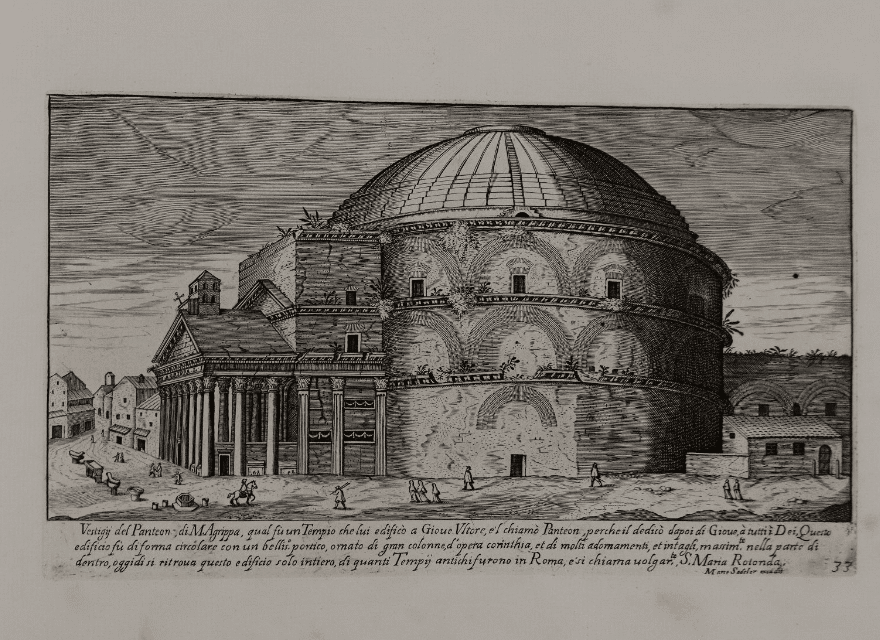

Personally, I find the second work bound in this volume much more fascinating: printed without a date but dating back to 1660, these “Vestiges of the antiquities of Rome, Tivoli, Pozzuolo and other places as they were found in the 16th century.” they look at ancient monuments with another eye: here the protagonist is 16th century Rome with views in which the Roman ruins fit naturally into the streets and squares animated by small figures that take us back to the life of the time; it seems no coincidence that these figures can often be identified with tourists admiring the remains of the ancient power of Rome. The typography is precisely that of Giovanni Giacomo De Rossi. This collection of prints actually takes up a previous work which had been very successful thanks above all to the fame of the engraver: also in this case the authors of the two editions are part of a single family, the largest and probably best known among the dynasties of Flemish engravers who worked in Europe in the 16th, 17th and following centuries, both as artists and publishers. The beautiful engravings in our volume are in fact signed by Marco Sadeler, who as we said reproduces, by re-engraving the branches, a previous work by another Sadeler, Aegidius, court engraver of Rudolf II, a work published in Prague in 1606.

Almost in a game of Chinese boxes, the 1606 volume was also in reality a reduced-format reproduction of another famous work, “The vestiges of the antiquity of Rome collected and portrayed in perspective with all diligence by the Parisian Stefano du Perac” , published in Rome by Lorenzo della Vaccheria in 1575: in all three editions we find the same 38 views of Rome, but, comparing the plates of Du perac to those of Sadeler, a different hand is clearly perceived: in the plates of the two Flemish engravers we find a style richer in chiaroscuro which gives greater depth to the views. And what’s more, the Sadeler version is not limited to the visit to the eternal city, but accompanies our travelers to other places famous on the Grand Tour for their beauty and their monuments: here are two views of Tivoli and seven romantic landscapes in the surroundings of Baia and Pozzuoli, to which are added, in a not exactly coherent juxtaposition, an image of Barland in Zeeland and a view of Vissehrad Castle in Bohemia.

It is always a great emotion to leaf through volumes like the one I have tried to describe to you: between the pages it seems to perceive the echo of the amazement and admiration of all those who preceded us in viewing such beautiful images. But ultimately that’s what happens with any ancient book you’re lucky enough to have in your hands.