The depiction of the Moors in art

The depiction of the Moors in art is a subject as wide-ranging as it is difficult to approach, not only because of the vastness of the phenomenon both geographically and temporally, but also because of its delicacy. Here, we will not focus on the figures of the 3 wise men and in particular Balthasar, but rather on their profane representation, thus opening up another type of argument.

Although we believe a more detailed analysis of the history of glass in the various eras is essential, here we will focus only on one of the fundamental stages, corresponding to the birth of artistic glass as we conceive it now, characterized by new forms and processing methods, in clear departure from the stylistic models turned to the past which until then had characterized European artistic glassmaking production.

In the lagoon city and the surrounding areas, in fact, these representations were very deeply rooted in the artistic imagination: one of the best-known examples can be recorded as early as the end of the 15th century, in the canvas painted by Vittore Carpaccio depicting the Miracle of the Cross. Here the figure of the Moor is relegated to a servile condition, as the gondolier of a noble squire, in a manner that will find even cruder results in later centuries.

In fact, even earlier, Andrea Mantegna in the Bridal Chamber had painted a series of figures looking out from the oculus and among these appears a face of a Moor with a turban, also in this instance relegated to the role of maid to the noblewoman beside whom she is portrayed.

This type of representation was particularly successful at the turn of the 17th and 18th centuries and the epicentre was undoubtedly Rome, the home of the Baroque with the figure of Gian Lorenzo Bernini and his quest for theatricality. The reference artist of the papal court and of the most important noble and bourgeois personalities of the capital city was the head of a well-organised boutique and in fact had numerous pupils and disciples, who took part in this style with its highly theatrical rendering, following the master’s concepts.

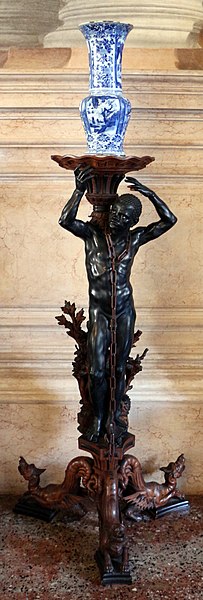

For our speech, a category of furnishings such as wall-tables deserves special mention: the structural part was in fact richly carved and if at first this consisted of powerful leaf volutes and characteristic curlicue motifs, towards the end of the century human figures or satyrs began to appear, often by the hand of a real sculptor.

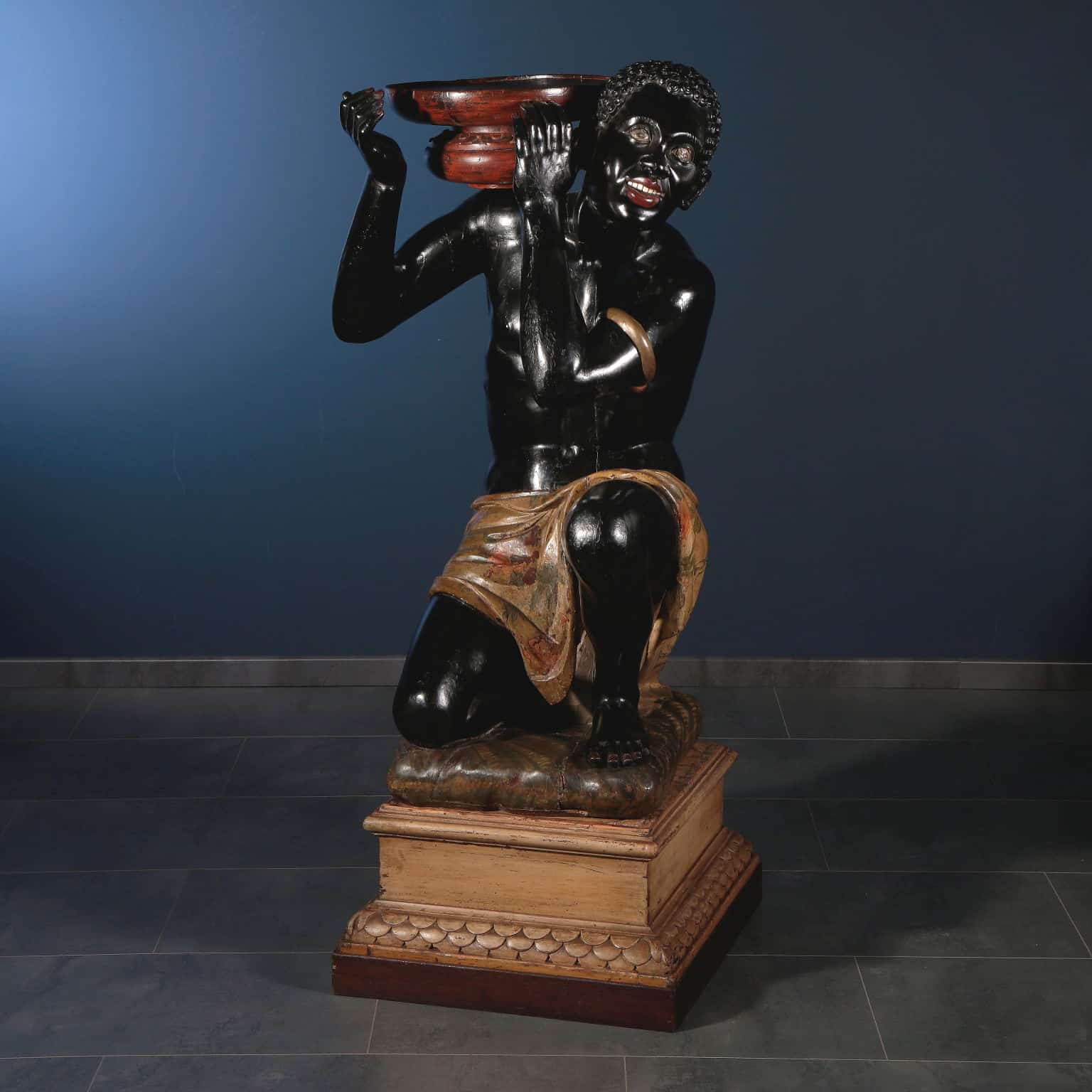

Among the figures often acting as shelf supports, depicted in crumpled positions and extreme effort to support the marble slab (or the structure above in the case of other types of furniture) are figures of Moors or Indians.

Perhaps even more so than in the past, this choice became an expression of a clear political intent.

The comparisons with the console tables in the Galleria di Palazzo Colonna, studied by Roberto Valeriani, are striking. Two of them in the Sala dei Paesaggi feature pairs of reclining slaves, by the hand of Isidoro Beati, while the remaining six (four in the Sala Grande and two in the Sala della Colonna Bellica), also with figures of Moors, are documented as the work of the sculptor Giovanni Battista Antonini and his atelier in the early 18th century. In this case, the term ‘Moor’ could be misunderstood to mean more generally that of a foreigner. More correctly in this case it is in fact Turkish, carved in the round in wood and gilded, alluding to the victory of the Christian troops over the Ottomans in the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, in the context of the Cyprus War.

Thus, it becomes clear that the depiction of Moors in an attitude of submission is linked to a desire to celebrate the supremacy of the European conquerors. Hence the tradition spread not only in the papal states, but also in the major European courts: it is not unusual to find Moors, Arabs or Indians depicted as prisoners, often chained and in a position of slavery.

The most recent studies show how this particular type of Moorish carving, used as furnishing accessories to support vases or lamps, was quite widespread on the Old Continent, certainly a symptom of a tradition that was all too well established.

In fact, a recently discovered pair of torchères carved in the shape of Moorish moorshorn holders, preserved at Ham House in Richmond and attested here since at least 1677, and for which it cannot be ruled out that they may belong to an English production (here the article).

Furthermore, a drawing for a guéridon by the engraver Jean Le Pautre where the support is a slave figure is now known, as well as a cabinet in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam proving that the use of moors in Dutch production was already established in the 17th century.

Returning to our peninsula, commissions of this kind are also to be found in the Medici sphere, among which we should mention the examples made for the ‘great prince’ Ferdinand in 1683 by Balthasar Permoser, and again those mentioned in the inventories of Palazzo Pitti as early as 1637, a pair for use as ‘lamp stools’.

As already mentioned at the beginning of this contribution, the depiction of Moors in furnishing accessories is, however, inextricably linked to Venice, certainly thanks to the local champion in the field of wood carving: Andrea Brustolon.

A pupil of Filippo Parodi during his stay in the lagoon, Brustolon’s trip to Rome was certainly formative for him, so much so that once he returned home he focused in the art of cabinet-making, clearly showing the Capitoline influence in using carved figures in the round as supports for furnishings. Famous examples are the works conserved at the Ca’ Rezzonico Museum, such as the armchairs of the Fornimento Venier, where Moors serve as the supporting structure for the legs and armrests, or the vase holder with a nude, chained Moor.

At this point, however, a clarification is needed. It was previously pointed out that the representation of Moors or Indians was intended to emphasise the dominance of Western culture and society. While this was certainly one of the main motivations, one must not forget the trade relations that Venice had historically entertained with other continents for hundreds of years. The depiction of these figures therefore also became a pretext to narrate that exoticism, given by the richness of the fabrics and feathered jewellery, that so fascinated and met the taste of the time.

Deeply rooted in lagoon figurative culture, this fashion continued throughout the 19th century; a particular appreciation can be seen in the second half of the century, in the context of the revival of stylistic currents of the past.

Pertinent with what was defined as Neo-Baroque, the production of this type of furnishing accessory underwent a further increase, often characterised by a choice of taste that was an expression of eclecticism, dictated by the heterogeneous figurative influences that occurred at the end of the 19th century.

Several Venetian companies specialised in wood carving in the neo-Baroque style are documented: the Sarfatti company (the mail order catalogue published in 1887 is well known), but also the workshops of Valentino Besarel (1829-1902), Vincenzo Cadorin (1854-1925), Marco del Tedesco (active in 1887) and Francesco Taso (active in 1878).

In conclusion, we would like to make a brief and personal observation. In recent years, these representational typologies have been analysed mainly because of the strong racial message they carry, downgrading them as expressions of a deplorable attitude towards certain ethnic groups.

As the art historian Hannah Lee already suggests, it is normal and proper that we ask ourselves questions about these representations, wondering how they can be interpreted by contemporary audiences.

In our opinion, the main point should be to understand them as descriptions of the culture of a specific historical period, expressions of a specific society characterised by dynamics and modes that are certainly morally to be condemned. Rejection and denial of these events, however, by concealing this particular category of artistic products would in our opinion be counterproductive. As history teaches us, concealing certain representations and, even worse, destroying them, does not lead to a true and mature reflection on them.

After all, iconoclasm has never led to anything good.