Chinoiserie and the charm of the East

Exoticism and chinoiserie, a fashion that developed in the eighteenth century with the advent of Rococo, but which spread widely with Neoclassicism and also in the following century.

The attraction towards the East is actually much older, already at the time of Marco Polo‘s travels, made famous thanks to the Milione. Knowledge of these places and very different cultures was possible thanks to the accounts of travellers, often traders, and the merchandise they imported. Precious spices, colorful fabrics, small finely decorated objects are the products with which we initially came into contact with Asian art and style.

In the 18th century, the real fashion for chinoiserie exploded. Trade exchanges increased, with the consequent importation of an ever-increasing number of oriental artefacts. These were appreciated both for their aesthetic appearance, extremely refined and decorative in Western eyes, and for their manufacturing techniques, often handed down as secrets from generation to generation. In addition to small objects, furniture such as coffee tables or fabric or rice paper panels used to embellish the walls of the large palace halls were imported. Already in the seventeenth century, the most important noble families were able to obtain these artefacts: in 1644 the inventories of the Valentino Castle describe tables, caskets and other objects “made in the Chinese style”.

More and more often, however, local workers, as well as artists of great caliber, specialized in the creation of works and furnishings in oriental style, created ad hoc for a specific client, thus reflecting their specific needs. These products are in fact characterized by a mix of styles: furnishings and accessories with Western shapes, which follow the prevailing fashion of the moment, such as the moving silhouettes of Rococo or the subsequent, more linear ones of Neoclassicism, but which are adorned with subjects that recall instead the eastern world. These decorations are often faithful to the original ones, but even more so they refer to an imaginative vision of the so-called Cathay, with an idealized conception of places and characters that correspond to a topos now rooted in the European collective imagination. The sinuous lines and calligraphic designs of oriental art are appreciated for the infinite decorative possibilities they offer, from small objects to large walls.

In the eighteenth century, France was the nation that dictated the law regarding fashion, with the taste of the sovereigns who, starting from the Sun King and followed by the worthy heirs Louis XV and XVI, saw a real identification of their name with a stylistic current. It was precisely under Louis XV, with the Rococo, that the royal palaces opened up to chinoiserie.

Among the most important examples of this era is “La Grande Singerie“, a boudoir of the Château de Chantilly decorated in 1737 by Christophe Huet, in which Asian forms and landscapes are clearly evoked, but with an ironic streak, representing anthropomorphised monkeys performing actions, to make fun of the defects of men. Already several years earlier, an artist of the caliber of Jean Antoine Watteau had decorated an entire room with oriental-themed paintings, at the Château de la Muette, which was unfortunately lost due to the renovation of the palace starting in 1737.

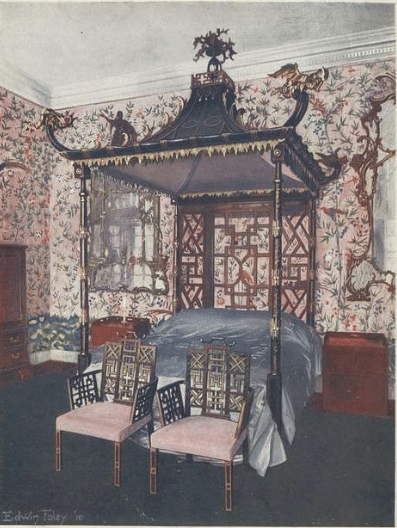

Together with France, one of the other countries driving this new fashion was certainly England. Widely appreciated by English royal families, an entire guest room with an oriental theme can be found at Badminton House as early as the 1850s, where the bed takes the form of a pagoda (Currently on site is a replica of early twentieth century, the original is preserved in the Victoria & Albert Museum in London).

But the one who more than anyone was the main promoter of chinoiserie was without a doubt King George IV. He promoted the construction of the Royal Pavilion in Brighton as a pleasure palace, deciding to set up some of the rooms in this style. The precise choice was to combine locally produced works with imported ones.

Furnishings, windows, carpets, furnishing accessories and furnishings with an oriental flavor were used in the Banqueting Room, the Long Gallery and the Music Room.

The walls of the latter were decorated with scenes of Chinese life, in gold on a red background, created by Frederick Crace and Henry Lambelet and taken from The Customs of China by William Alexander.

The fashion for chinoiserie proposed by these two great powers influenced, sooner or later, also the other European courts.

One of the most receptive areas was certainly Piedmont, where several royal environments decorated in chinoiserie can be appreciated.

Already in 1733 the works for the Chinese Cabinet for the Royal Palace of Turin, built under the direction of Filippo Juvarra at the behest of Carlo Emanuele III, are widely documented. On this date the documents show the purchase of the lacquers (which actually took place the previous year), also bringing out an interesting aspect, which confirms a further line of this production. In fact, the architect appears to be aware that they are lacquers from “Gappone China”, i.e. oriental imported products specially made for the European market, therefore with decorative motifs that further emphasize those characteristics so appreciated in the West, such as the details naturalistic and color contrasts.

Juvarra was able to adapt and harmoniously blend this exotic fashion with the rocaille shapes that were becoming established, specifically choosing gold lacquers on a black background and skilfully integrating them with natural elements.

But other construction sites also fell under the spell of the East. An entire Chinese apartment was in fact arranged in Raccongi at the behest of Ludovico Vittorio of Savoy, Prince of Carignano, where the walls covered in rice paper painted in watercolor with scenes of life, imported in the mid-eighteenth century directly from London, can be appreciated. A few years later, the purchase of “Chinese Papers” by the Savoy family for the Royal Castle of Moncalieri is known.

But the fashion for chinoiserie had now spread to the rest of the peninsula too. Remaining in Northern Italy, one of the most interesting examples is that of the country villa of Count Donato II Silva, in Cinisello (MI).

An entire Chinese apartment was set up here, of which no trace remains today, but we can only learn about it through the description made by his nephew Ercole Silva, from the early nineteenth century. Consisting of two rooms and three bathrooms, the wall paintings with landscapes by the painter Carlo Caccianiga are documented, while the overdoors were created by Agostino Gerli. Noto is a group of furnishings, consisting of consoles, chairs and sofa, in which the uprights are in the shape of Telamons dressed in oriental style and which, presumably, were made precisely for this client.

Moreover, even a cabinetmaker of the caliber of Giuseppe Maggiolini, in the creation of one of his most valuable furnishings and used no less than as a gift from Archduke Ferdinand for his mother Maria Teresa, the desk now in Vienna, inserted reserves inlaid with scenes of Chinese life.

One of the most spectacular and rich examples, however, is certainly the porcelain sitting room built in the 1750s for the royal apartments of the Queen of Naples Maria Amalia of Saxony in the Royal Palace of Portici and transferred in the 19th century to the Royal Palace of Capodimonte, where it is located today again. A true jewel of local manufacturing, the walls are entirely in painted porcelain, thus evoking refined decorations and characters of chinoiserie taste not only in style and subjects, but also in the material, traditionally linked to the East.

To conclude this brief overview of some of the most significant examples of European chinoiserie, a later but certainly significant example is the Chinese Casina (also known as Palazzina) in Palermo. Built for Ferdinand III of Sicily by Giuseppe Venanzio Marvuglia starting from 1799, it is characteristic that the appreciation for the oriental style is not only found in the interior spaces, but also in the architecture of the building itself, in particular in the pagoda roof.

If chinoiserie gradually saw their decline as a style chosen by royalty and nobles for the construction of some of their apartments, today they are instead highly appreciated and sought after for the refinement of execution, the exoticism that they are able to evoke and above all for the elegance that distinguishes them.