The Universal Exhibitions

1851 was a fundamental year not only for the history of art but also for the history of industries and crafts. In this year the famous Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations was held, better known as the first great Universal Exposition, organized by the architect Henry Cole, with the support of Prince Albert.

A cast iron and glass structure specially made for the occasion was set up in Hyde Park in London, inside the Crystal Palace. The purpose of the exhibition was to present what was most up-to-date in the field of applied art and industrial production; the participation from all over the world was massive, there were in fact 13937 exhibitors, despite some famous defections such as that of Thomire or Deniere, famous French bronze workers who did not want to make their production techniques known.

With the Industrial Revolution and the advent of the new social class constituted by the bourgeoisie, more people had access to goods previously considered luxury.

In furnishing their homes, the bourgeois showed great attention to the aesthetics of objects and furnishings. Consequently there was an adaptation of production towards this address. The figure of the designer began to assert himself, in charge of designing objects not only for their functionality but also for their aesthetics.

However, if the cast iron and glass building, designed by the architect Joseph Paxton, denoted a notable consideration for innovative forms and materials, what was exhibited presented a very different panorama.

All the works and objects, including those of industrial production, were inexorably affected by the styles of the past. The numerous criticisms that followed and which highlighted the backwardness of taste, as well as the lack of creativity, led Cole to strongly promote and support the intervention of artists in the design phase.

The following year the Museum of Manifactures was established, whose collection was constantly updated with the latest news, both to inspire designers and to educate the public’s taste. The museum, which was none other than the first nucleus of what would later become the Victoria and Albert Museum, was also supported by a drawing school applied to industry, further proof of the importance of a production of objects that had a precise stylistic design.

In England this exhibition had an enormous influence on art and industrial production.

In the second half of the nineteenth century the famous Arts and Crafts movement was born, based on a reform of applied arts in the light of mass production, a consequence of industrialization. Faced with a standardization of objects, the founder William Morris, a follower of John Ruskin, promoted a return to the creation of objects (carpets, upholstery, fabrics but also furniture) on the basis of the old artisan concept. This did not imply that modern equipment was completely rejected, but that the artist, a new designer, took care of the design of the drawing, while in the realization the value of the materials used should have been taken into account.

In this regard, Morris wallpapers are famous. Unfortunately, this production did not have the hoped-for success, since it still offered items at too high and niche prices for them to be widely diffused and to carry out that much desired re-education of taste.

The experience of the Universal Exposition and of the Arts and Crafts, although not completely successful or which in any case had raised several problems, was fundamental. In contrast to the mass production of objects solely for their functionality, the main criticism that emerged was the need to return in some way to the artisan sphere. The artists had to deal with an aesthetic of the applied arts and use the new industrial means in their favor to make them accessible to as many people as possible.

The echo that the 1851 exhibition had worldwide was enormous. Similar initiatives were immediately promoted in the main European cities.

If on the one hand these fairs were a real presentation of what was most avant-garde in the world, on the other they were characterized as a sort of pretext in which the various nations wanted to present themselves as the most innovative and bearers of a modern taste and attentive to the aesthetic result.

The next one was in fact held in Paris, in 1855, with the specific intent of overcoming the results obtained by the Londoner forerunner.

This will was already clear from the exhibition venue. The French built the Palais de l’Industrie, clearly rivaling the superb architecture designed by Paxton. It was the first exhibition to explicitly foresee a pavilion dedicated to fine arts, famous for having included, by one of the great rejects, Gustave Courbet, the much better known Pavillon du Réalism.

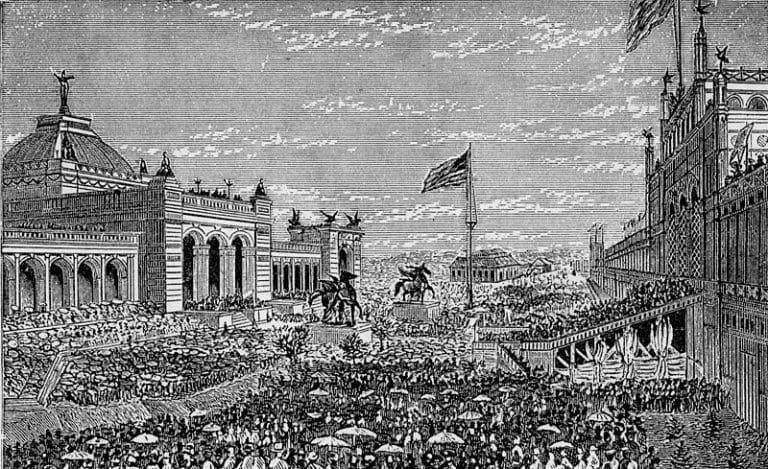

More than twenty years after the first Universal Exposition, in 1876 the Expo was held in the United States, on the occasion of the centenary of the American declaration of independence.

This fact was very important: if until the middle of the 19th century the epicenter was still substantially European, with the end of the century we began to anticipate the reversal of the equilibrium that would be affirmed in the 20th century. The United States did not shyly face the world political and cultural landscape, but laid the foundations of what would have been a true cultural hegemony.