The protagonists of the Savoy Restoration between Piedmont and Liguria

The 19th century was characterised by an upheaval in society and, consequently, in cultural and artistic events too.

The roots of this change actually trace back as far as the end of the 18th century, with an event such as the revolution that had questioned the political and social balance not only in France, but in the whole of Europe, questioning and deposing one of the oldest and most powerful royal families. It was not a matter of wars between powers for the annexation of territories, the entire social balance had been compromised.

One of the dynasties most affected by these events was that of the Savoy family: literally driven out by Bonaparte, they saw their palaces stripped by the French occupation, although often refurbished in the much appreciated Empire style.

After their returrn, they began to reorganise their residences, primarily the Castle of Racconigi, that of Pollenzo and the flats of the Royal Palace, entrusting the task to Pelagio Palagi, appointed in 1832 by Charles Albert as ‘Painter in charge of the decoration of the Royal Palaces’, specially instituting this “ex-novo” title.

With this prestigious assignment, the architect was able to realise works that demonstrated his high inventive ability without detracting from aesthetic refinement.

The reference models were Piranesi’s prints, certainly mediated through a personal interest in and study of archaeology, resulting in elegant reworkings capable of combining neoclassical elements with others typical of the Restoration and quotations from antiquity.

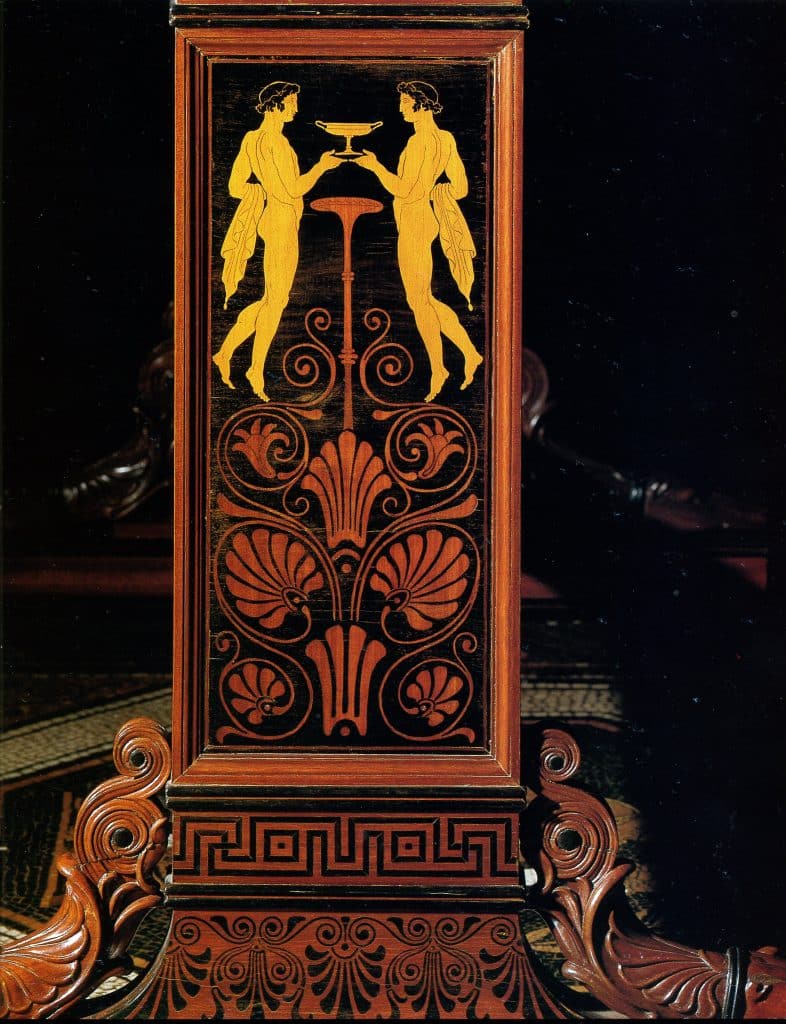

A true revival of classicism, recalling the neoclassicism of the late 18th century now influenced by the imperial interlude through a decoration rich in historical references. One of the finest examples of this is the King’s Etruscan Cabinet, built at Racconigi Castle or, again at the same venue, the Apollo Room. But his projects also had the merit of being anticipators of those revivals of past styles that became popular at the end of the century, in particular the neo-Gothic tendency that can be appreciated in his interventions such as the Pollenzo Castle and the Margaria, also in Racconigi. On these occasions, Palagi showed himself to be up-to-date with the modern European taste.

One of the main cabinet-makers able to absorb this taste and translate it into refined carving and equally painstaking marquetry was Gabriele Capello known as Moncalvo (1806-1876). Initially called upon by Maria Theresa to make the high chair as a birthday gift for her consort Charles Albert, he was later directly involved by Palagi himself in the creation of some of the royal furniture, such as the chairs made to his design, for the aforementioned Etruscan Cabinet.

His works for the Savoy family were in fact countless: floors, furniture and, certainly not least, the throne itself for Charles Albert in the Royal Palace. His fame and skill were such that in 1858 he was awarded the title of His Majesty’s Ebonist and Cabinetmaker, and was allowed to use his letterhead only four years later.

n introducing the figure of Moncalvo and his works, however, one cannot overlook his personality, and in particular his focus on teaching and social issues. In addition to innovations in workmanship and constant research aimed at improving his technique and thus the quality of his works, Capello also paid special attention to the training of new generations.

his took place not only within his workshop, as was the practice, but also through the foundation of the Scuole Operaie San Carlo and, a few years later, the Royal Industrial Museum of Turin, precisely to pass on skills to new and emerging cabinet-makers. But his attention to carvers was not only directed at the very young: in 1865, he set up the Capello/Moncalvo ‘L’Amor Fraterno’ (Brotherly Love) Fund, aimed at guaranteeing pensions to artisans who had become unfit for work.

However, the “Palagiani” teachings were not confined to Piedmont alone, establishing themselves in the rest of the peninsula as well.

Among the areas that were most influenced by Pelagio Palagi was undoubtedly Genoa, as demonstrated by the refurbishment of the Royal Palace, where local artists who looked to the architect’s work as a reference model were active.

Among the leading figures in Genoese cabinet-making, Henry Thomas Peters (1793-1852) must undoubtedly be remembered. An Englishman by birth, he arrived in the Ligurian city in 1817, immediately achieving a fair degree of success, thanks to the commission for the furnishings of the Villa Durazzo, being introduced into the city’s main circles by the same family.

His boutique was characterised by an innovative approach, a true forerunner of more modern production: in addition to several steam engines, the figure of the qualified worker began to be identified, who, according to his personal predispositions, focused on the production of a single piece of furniture for subsequent assembly, rather than dealing with the whole piece of furniture.

This seriality, together with the use of more modern instrumentation, a special planer brought from the mother country and useful for cutting mahogany plates, also allowed him to offer a series of furniture at lower prices, as he himself advertised.

In 1833, he began his direct collaboration with Pelagio Pelagi, as the dense correspondence between the two shows. His commissions were various: Villa Durazzo, the Council Chamber of the Royal Palace, Racconigi and many others, establishing himself as one of the most sought-after and appreciated cabinet-makers of the time.

Despite these successes, his career was so much fragmentary that financial straits forced him to dissolve the firm in 1849 and his funeral, three years later, was supported by the Società di Mutuo Soccorso fra Ebanisti e Falegnami.

His style is characterised by a reinterpretation of the typical taste of the Restoration, mediated by Palagian teachings, resulting in furniture and ornaments characterised by rigour and simplicity of line, but still characterised by a sober elegance and high quality construction, certainly derived from the English Regency. In particular, this characteristic was translated into great accuracy in the realisation of the joints of the furnishings, as well as in the choice of materials and locks, producing furniture that took into great consideration the practicality and functionality of the same, with dimensions that were often contained and therefore well suited to the demands of the emerging bourgeoisie class.

Pair of containers for geographical atlas, Henry Thomas Peters