Mannerism

Mannerism is a passing cultural and artistic current, directly derived from the Renaissance and which lays the foundations for the subsequent Baroque style.

Historically, Mannerism was born at the beginning of the fourth decade of the sixteenth century and, as the name itself indicates, is characterized by an art “in the manner of” (that is, in the style of) the great protagonists of the Renaissance. The references are primarily artists of the caliber of Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael and Michelangelo. The Mannerist artists and painters in fact took up the style, in some cases simply copying it and therefore initially involving a negative meaning of the term. Others were instead able to re-elaborate and adapt “the manner” to their own historical and cultural context.

The Renaissance was in fact characterized by the centrality of a man and the domination of scientific rigor, which in art was translated into perspective representation and the search for naturalism.

The sixteenth century was instead studded with historical events that influenced thought and culture, inevitably modifying the attitude towards the arts.

Among the main events there were certainly the great epidemics of plague, the sack of Rome in 1527, and the Counter-Reformation, culminating in the Council of Trent (1545-1563), in order to oppose the Protestantism promulgated by Martin Luther.

These events questioned the infallibility of human science and rediscovered a new religiosity.

These changes could only be reflected in art. The human figures in the paintings are no longer naturalistically represented but the anatomies lengthen, as in the case of the famous Long-necked Madonna by Parmigianino, where the Virgin but above all the Child have unrealistically elongated bodies. The relationship between man and architecture has also completely changed. The remains of classical antiquity are no longer ideal reference points, but loom over man almost like a warning and are often depicted with a perspective distortion.

The composition lines of the scenes also change. The symmetry and modularity in fact give way to more chaotic scenes, in which the bodies assume twisted and unnatural positions.

One of the most famous examples is Pontormo’s Deposition, also due to the acid palette that the painter used, which contributes to moving away from a naturalistic representation.

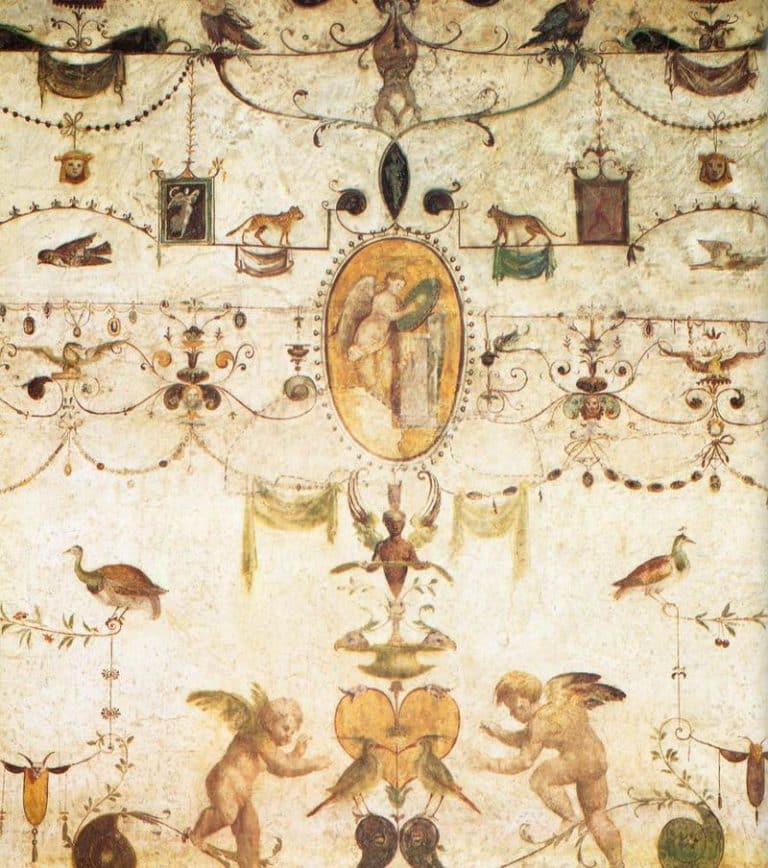

The reference to the past, albeit to its most fantastic version, is also found in the ornaments. In the decorative arts, the mathematical care of

the perspective realization of objects also undergoes an imbalance in favor of decorative abundance.

In the sixteenth century, in fact, the grotesque decoration spread, characterized by the union of plant elements and monstrous animal or anthropomorphic figures. Various elements are joined together for pure decorative taste, without any meaning or conceptual logic. The name derives from the place where this decorative typology was discovered, namely the Esquiline caves, which were none other than the rooms of Nero’s Domus Aurea. The grotesque is inexplicable, disturbance of the order.

Many artists used the grotesques in the wake of the enormous fortune that Raphael and his workshop brought there, as in the case of the Loggetta del Cardinal Bibbiena (Vatican, Apostolic Palaces), a model for painters up to the late sixteenth century.

This decorative typology also became a decorative element in the so-called minor arts, on the pilasters of the buildings, in the carvings or inlays of the furnishings, on the gold workings of precious objects.

In summary, Mannerism is a stylistic current which, if at the beginning it is characterized as a re-proposal of the styles of the great Renaissance artists, it continues instead by distancing itself further and further.

The mighty Michelangelo figures stretched out in serpentine positions are taken to extremes and placed in unbalanced postures, which in some way reflect the uncertainty and loss of faith in science and nature that had instead characterized the Renaissance man.