Humanism: the invention of the book

What is considered by many to be the most beautiful book in the history of printing, the mysterious Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, was published in Venice by Aldus Manutius in 1499, at the end of a century that saw the birth of the modern book within the cultural context of Humanism.

But what is the relationship between these two central aspects of the fifteenth century?

In a letter to Cardinal Juan de Carbajal of 12 March 1455 Pope Pius II (the humanist Enea Silvio Piccolomini) writes that he saw in Frankfurt the loose files of a Bible not written by hand but printed: it is the beginning of the great revolution of Gutemberg which immediately spread throughout Europe. The discovery of a new, entirely mechanical way of writing makes it possible to reproduce texts by responding to the ever-increasing demand for books by urban society in the new climate created by Humanism.

Humanism is often identified with the great rediscovery of ancient, and especially Greek, authors, also linked to historical events such as the fall of Constantinople in 1453.

In reality, classicism, and even Greekness (think of Aristotle’s centrality in the philosophical field), were not unknown to the Middle Ages: what changes are not so much the contents, but the forms of a culture, the attitude towards the culture of past.

The new approach to ancient texts, which founds modern philology, leads to a conquest of the sense of the ancient as a sense of history.

Paradoxically, the Humanists discover the classics because they detach them from themselves. The Medieval vision of the static, ahistorical real, object of contemplation, of the canonical texts bearers of Truth (ipse dixit), is overcome by a way of reading every document, paper, book, considering that, as it is presented, it is a fact human, a trace and a human resonance, and as such subject to scrutiny and critical reading. And then there is no longer an immutable text, to be terminated indefinitely, there is no longer a Truth simply to illustrate: the ancient world speaks of man, of the risk of an adventure of which error and doubt, but also the possibility of discovering, starting from there, a new way of reading reality.

Hence the anthropocentrism that distinguishes the thought of Humanism: as Eugenio Garin says

“The discovery of the ancient world cannot be distinguished in Humanism from the discovery of man because they were one, because discovering the ancient as such meant commensurate oneself with it and detaches oneself from it and puts oneself in relationship with it. It meant time and memory, and a sense of human creation and earthly work and responsibility”.

It is perhaps no coincidence that the invention of printing takes place at this very moment: the same novelty of gaze reserved for texts also invests the physical, concrete medium that allows texts to exist.

The traditional reproduction process is reinterpreted by the first printers, analyzed, broken down into its basic elements, to give life to something new that changes the very status of the book. The book ceases to be an almost sacred object, reserved for the restricted world of the Church and of power, a symbol of an esoteric conception of the world: no longer the result of the traditional method of copying, the printed book becomes the model of a new way of conceiving the work, of designing using new technical and mental procedures, to create what will prove to be the main means of diffusion of a new way of thinking about the world.

The first book printed in Italy is Lattanzio’s “De divinis institutionibus adversus gentes”, printed in the monastery of Subiaco in 1465 by two German clerics, Corrado Schweinheim and Arnolfo Pannartz, pupils of the German printer Schoeffer.

Soon the new technique spreads across the peninsula, but it is in Venice that it finds the ideal place for its flowering. And it was in Venice that the man who more than any other represents this union between culture and technology, a crucial moment of passage in the history of Italian and European culture, worked: Aldo Manuzio.

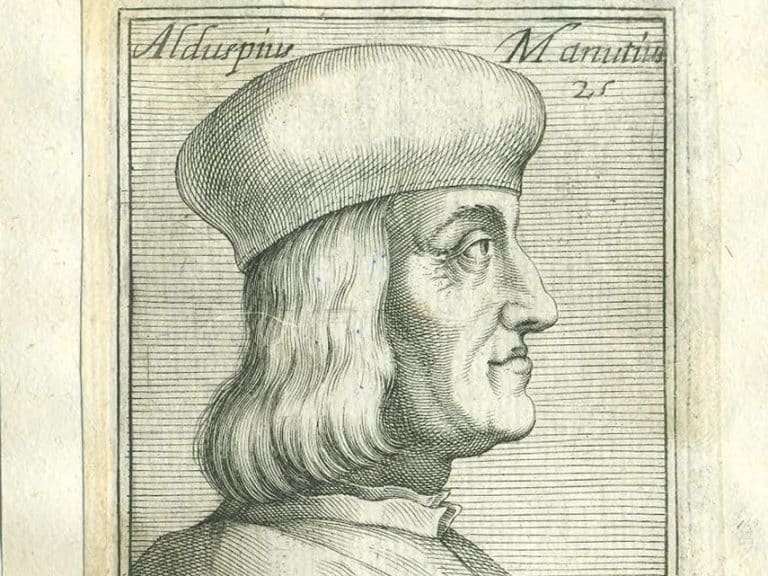

Aldo arrived in Venice already forty, around 1490. In his history, years of study, first in Rome, then in Ferrara, where he studied Greek, relations of friendship and esteem with the major representatives of Italian Humanism: the letters with Poliziano and with Pico della Mirandola, who advises him to the widowed sister of Lionello Pio, lord of Carpi, as a tutor for his children. A solid career as a scholar and teacher that Aldo suddenly left to throw himself into the complicated world of publishing in the Serenissima.

What are the reasons for this choice, at an already advanced age? Certainly Aldo sees far and perhaps senses that his ideal of disseminating knowledge as a tool for reaching a deeper humanity can be achieved more effectively by working on the tools of this dissemination, and therefore on the relatively new world of printing.

In Venice he moves as a great entrepreneur: he enters into partnership with the printer Andrea Torresani who in 1479 had taken over the historic printing house of Nicholas Jenson, and from here he launches his great cultural project: to relaunch the study of the great Greek classics, committing himself to supplying tools learning (the first book published is the Greek grammar of Lascaris in 1494) and above all accurate editions of the texts.

The first tome of the Works of Aristotle dates back to 1495, a large in-folio, the beginning of his most ambitious project. In fact, if they had asked Aldo, at the end of his life, what his most beautiful book was, he would probably not have mentioned the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, the dream of every contemporary bibliophile, printed for more clearly “commercial” purposes, but precisely the Aristotle’s edition or that of Plato, which instead proved to be a near failure commercially.

A group of young and old scholars from the Greek world gathers around Aldo’s printing house: after all, the mythical Cardinal Bessarione already in 1468 defined Venice as “a second Byzantium”: which city more favorable to Aldo’s dreams? Among the figures who frequent the noisy printing house in calle San Paterniano stand out key figures of the culture of the time: Erasmus of Rotterdam, who settled there in 1508, the year in which he published the Adagi for the types of Manutius, and then published in 1515, the ‘In praise of madness; Pietro Bembo, very close collaborator of Aldo, who finds his ally in the printer to carry on his battle for the definition of the Italian vernacular (1505 is the publication of the Asolani).

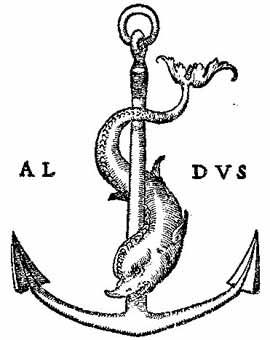

The catalog of books marked with the anchor and the dolphin mark is a succession of Greek and Latin titles, but there is no lack of Petrarch, in the edition edited by Bembo in 1501, and Dante with the Terze rime (i.e. the Comedy) of the 1502.

But beyond the cultural relevance of the philologically well-finished editions that come out of Aldo’s printing house, what remains as his greatest contribution to the history of publishing are his technical innovations.

The creation of typefaces of still unsurpassed beauty and legibility (the Bembo of De Aetna of 1496, but above all the italics drawn by the goldsmith Francesco Griffo) and above all the publication of volumes in -8 ° that completely change the relationship between reader and book. Until now, the prevailing format had been the large in-folio or the in-4 °: large, unwieldy volumes, very expensive, which trivially required the use of a lectern. Aldo’s great idea is to publish the texts of Greek, Latin and Italian authors, the pure text, without critical apparatuses, in what he defines as Enchiridia, librettos that fit in the hand or pocket, which can be read anywhere, in any moment. The publication of Virgil’s works in italics and in-8 ° in 1501 changes the way of living reading forever and makes the book what it is still today for us.

We do not know if Aldo really imagined a world in which books could become everyone’s heritage, beyond social and economic distinctions. What is certain is that in Utopia, the mythical island dreamed of by Thomas More in 1516, the inhabitants own only Aldine editions.

Bibliography:

– Eugenio Garin – Italian humanism

– Giorgio Montecchi – The Renaissance: The press and dissemination of scientific knowledge

– Martin Lowry – The world of Aldus Manutius

– Giacomo Comiati – Aldo Manuzio: editor, humanist and philologist

– Max Trimurti – Aldo Manuzio, humanist editor in Venice