Herculaneum, Pompeii and the Royal Bourbon Museum

“There is something prodigious in a city that after centuries returns to the light of the sun”

With these words Mario Praz, in his book Gusto Neoclassico, revives the enthusiasm that was aroused at the time by the rediscovery, under the layers of solidified lava, of Herculaneum and Pompeii, the two Roman cities buried by the disastrous eruption of Vesuvius in 79 BC.

A chance discovery: in 1709, during the excavation of an irrigation well, fragments of alabaster and precious marbles resurfaced. Further excavations bring to light columns, inscriptions, marble statues. The first systematic research began in 1738, commissioned by Charles III: Herculaneum resurfaces. In 1748, under Civita, here is Pompeii.

News of the findings travels around Europe: artists, scholars, writers, but also the young wards of the nobility engaged in the canonical Grand Tour, flock to see the excavations and the finds.

Goethe, Italienische Reise: “Naples, 13 March 1787 On Sunday we were in Pompeii. Many accidents have occurred in this world, but none capable of bringing such satisfaction to posterity. So far I have not seen anything more interesting than that buried city.”

The Neapolitan discoveries join the contemporary Roman ones, the establishment of the great collections of the Pio-Clementino Museum, wanted by Popes Clement XIV and Pius VI to collect the most important Greek and Roman masterpieces kept in the Vatican, the arrangement of the collections of the Albani and Borghese, to give life to a new artistic movement, Neoclassicism, which found in antiquity the ideal expression for its values of balance, composure, measure. Winckelmann’s studies, which culminated with the publication of the Geschichte der Kunst des Altertums in 1764, consecrated the new ideal of universal Beauty.

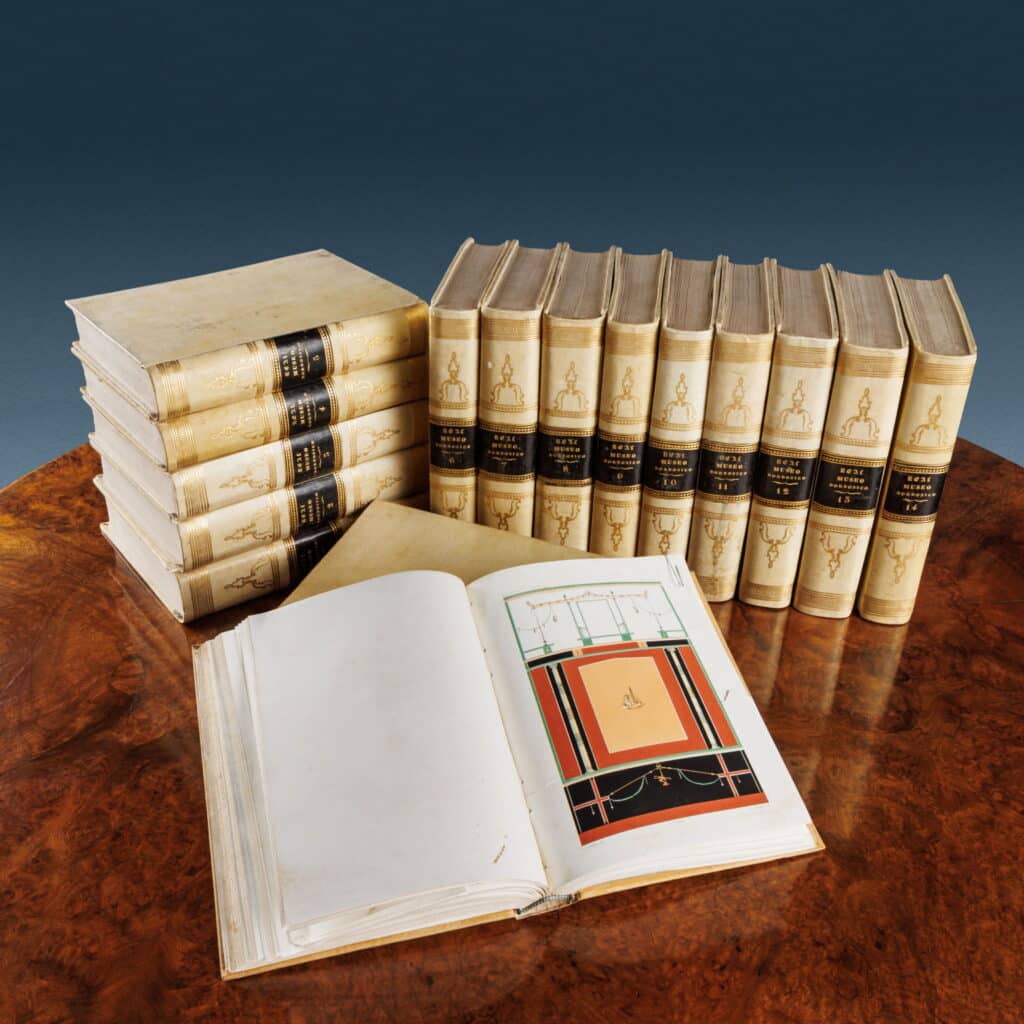

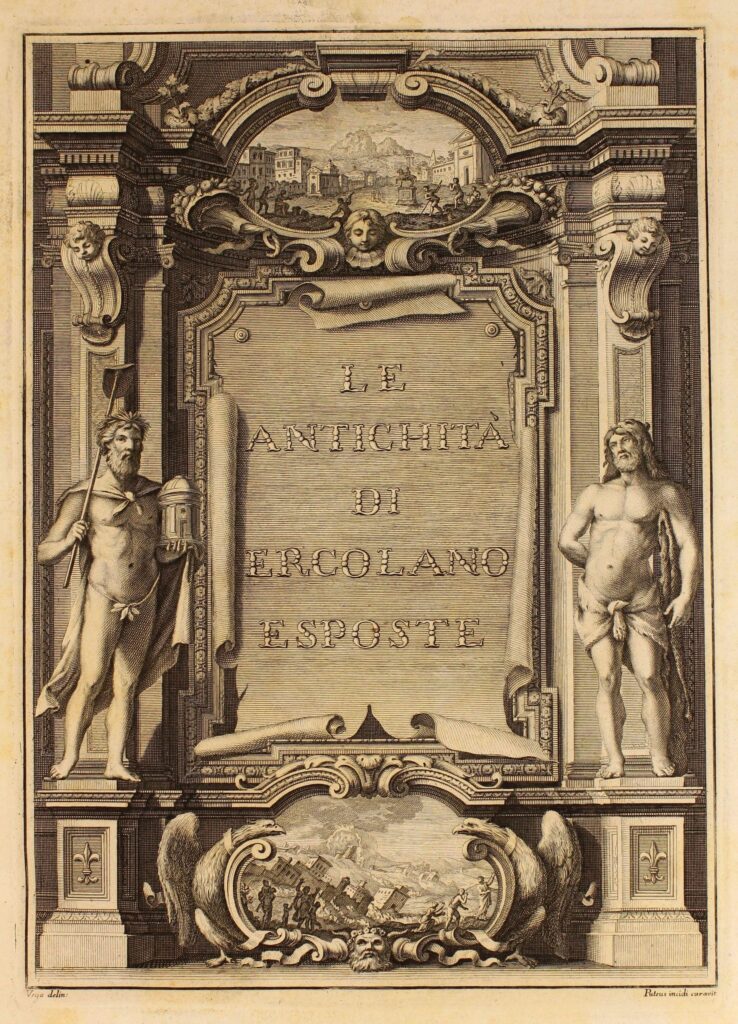

A central role in the diffusion of the new taste is entrusted to the art of engraving. The new discoveries of Herculaneum and Pompeii, collected in the royal collections of the Museum of Portici, were protected by a rigorous copyright by the Bourbon court: it was not possible to obtain authorization to draw from life in the excavations and in the museum. Here then are the eight large folios of the Antiquities of Herculaneum on display, published between 1757 and 1792, reproducing with accuracy, clarity and rationality all the eighteenth-century finds and paintings found. The volumes, not for sale but exclusively honored by the King at his pleasure, become the highly sought after source of the decorative motifs of painting, sculpture, ancient furnishings re-emerged from the lava: countless copies, especially of the first four volumes, dedicated to painting, invade the ‘Europe.

Grotesque wall decorations that had already so influenced Renaissance artists are forcefully back in vogue: think of the Raphaelesque loggias in the Vatican palaces.

Every European court wants to have its own “Pompeian” room: frescoes, decorative panels, tapestries, from Paris to London, up to the palace of Catherine II in Tsàrkoje Selò, are filled with Hellenistic motifs that resurface from the lively rediscovered paintings, with mythological subjects , of fantastic architecture, of trompe-l’oeil.

Through catalogs and image repertoires, ancient finds become models for artists and furniture creators: from the initial passion for the archaeological discoveries of a restricted aristocratic society we move on to mature neoclassicism which informs the bourgeois world.

In 1762 Abbot Galiani wrote from Paris to Bernardo Tanucci, minister of the King of Naples: “There are already all the furniture of the house à la Grecque, snuffboxes, fans, clocks, and even the signs of the shops…On the fireplaces, in exchange for the Chinese or Saxon porcelain figures, gilt bronze tripods are seen”; embroideries for clothes are obtained from Vitruvius, the engravings of Flaxman, Fontaine and Denon provide models for the ceramics of Wedgwood and Sevres; the table service from the Royal Factory of Capodimonte, a gift from Ferdinand IV to his father Charles III in 1782, eighty-eight pieces including plates, terrines, vases and triumphs, is all a copy of Herculaneum works; materials and ancient execution techniques are brought back into vogue: the reuse of ancient marbles translates into the creation of precious colored marble tops with complex geometry or in the composition of highly refined micromosaics. In this widespread diffusion, the modernity component of the neoclassical movement resurfaces, which combines the needs of rationality and sociality, in a enjoyment of Beauty that affects all objects of everyday use and not just the highest artistic creations, the prerogative of restricted social groups.

We can then only imagine the expectations aroused by the publication in 1824 of the first volume of the Catalog of the Royal Bourbon Museum, custodian of all the discoveries of the Campania excavations. This is the strong point that is highlighted in the presentation of this monumental work which will ultimately consist of 16 volumes: “The Royal Bourbon Museum, rich in illustrious works on a par with the most celebrated in Europe, surpasses all others for Monuments that they make it unique in the world; and they are those who, buried and preserved with entire cities by the nearby Vulcan, rise again after eighteen centuries to induce wonder and delight in the cultured nations”. Ferdinand I was the promoter of the publication, the first authorized of the Museum’s works, in which he “allows that the Royal Bourbon Museum be made public due to the unreserved prints of the things found in the excavations, which until now have remained unpublished due to the ban to draw them” which had been in force since the first excavations in Herculaneum for all the finds owned by the royal house.

But it is not just the finds from Pompeii and Herculaneum that make the catalog of the Bourbon museum unique: in the rooms of the Palazzo degli Studi (current seat of the National Archaeological Museum of Naples) Ferdinando brings together the immense riches of the Farnesian collections, inherited from his father Carlo , who had stripped the Duchy of Parma of the prestigious collections of Renaissance paintings between 1735 and 1739, and by her grandmother Elisabetta Farnese, with her collection of antiquities transferred from Rome to Naples between 1786 and 1788 despite the pope’s opposition Pius VI.

And so, as announced in the presentation of Vol. furnishings, vases commonly called Etruscan, weapons, engraved gems and medals, coins, oriental, Egyptian and Low-Time monuments and other objects of various kinds”.

The works are presented in 973 copper engraved plates, some lithographed in chiaroscuro with evocative views of Pompeii. The presentation criterion chosen is that of a mixture of works from different eras and genres, without chronological order, above all because in the meantime the discoveries of the excavation sites continued. Very interesting then is the presence, at the end of each volume, of the Reports on the excavations of Pompeii which directly follow the progress of the works in conjunction with the printing of the individual volumes, from February 1824 to December 1855.

If we think of the emotion that the media news of the discovery of new masterpieces in the inexhaustible excavation campaign under Vesuvius still arouses today, we can imagine the anticipation that accompanied the publication of each of the 16 volumes of the catalog among scholars and amateurs.