From drawing to marble: Antonio Canova

Marble sculpture is one of the most complex artistic forms. Its realization, unlike terracotta, in fact involved a subtractive type of processing. The artist had to intervene with chisels and hammers on the stone block, first roughly roughing out the volumes, and then intervening with chisels useful for defining the details.

Great attention had to be paid not to remove more than necessary, any errors could be compensated with plaster inserts, which however affected the value of the work. The choice of the marble block was also very important, as during the processing cracks or splits could occur at the height of the stone veins.

As is well known, marble sculptures saw their golden moment in Greco-Roman antiquity, albeit with an effect far removed from what we are used to. The findings of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries brought to light the works in which the marble was visible, with that candid effect that was so highly praised. Studies conducted in the twentieth century have instead shown the presence of polychrome traces. The statues were in fact completely painted, to create an effect of greater mimicry.

Precisely on the wave of the fortune of ancient statuary, this artistic technique was particularly appreciated starting from the Renaissance with great personalities such as Michelangelo, then passing to the Baroque with Bernini and, almost two centuries later, Antonio Canova.

The latter was one of the spokesmen of the neoclassical culture, characterized precisely by a rediscovery of the ancient, in the wake of Winckelmann’s theories, according to which Greek art was an expression of “noble simplicity and quiet grandeur”.

Thanks to the precious archive of works left by Canova, it was possible to study the operating methods of his workshop for the creation of marble sculptures. If such procedures can also be hypothesized for the other sculptors, including the famous names mentioned, it is with Canova that we are witnessing a real rationalization of the process, also in light of the hegemony of the Enlightenment culture.

The first phase was certainly that of conception. The choice of the subject, usually indicated by the clients, and the elaboration of the positions of the characters were represented in drawings. These studies included different representations from different points of view, to try to analyze on a two-dimensional support what would later be a three-dimensional work, usable from multiple angles. As mentioned, being one of the spokesmen of neoclassical art, Canova often took inspiration for this first phase from ancient works, both sculptures and paintings, as for the drawing of Cupid and Psyche (preserved at the Civic Museum of Bassano del Grappa) , taken from a sketch of Herculaneum depicting a Faun and Bacchante and translated into various engravings.

The artist then proceeded with the creation of a terracotta model, in order to analyze the yield of the volumes and above all the chiaroscuro effects of a three-dimensional object. These models were considered by Canova as real personal studies, so much so that he jealously kept them inside the wardrobes in his study.

The sculptor then proceeded to create a life-size clay model, finished as much as possible. This was covered with a plaster casing, in order to create the shape inside which plaster was in turn poured in liquid form and, once solidified, a sculpture was obtained almost identical to the final marble sculpture.

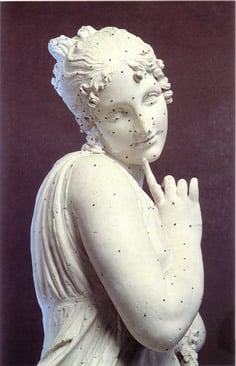

Canova’s careful workshop therefore proceeded with the application of repère, bronze nails placed symmetrically and at a precise distance from each other.

Some, called key points, were more protruding than the others to indicate the maximum dimensions of the statue.

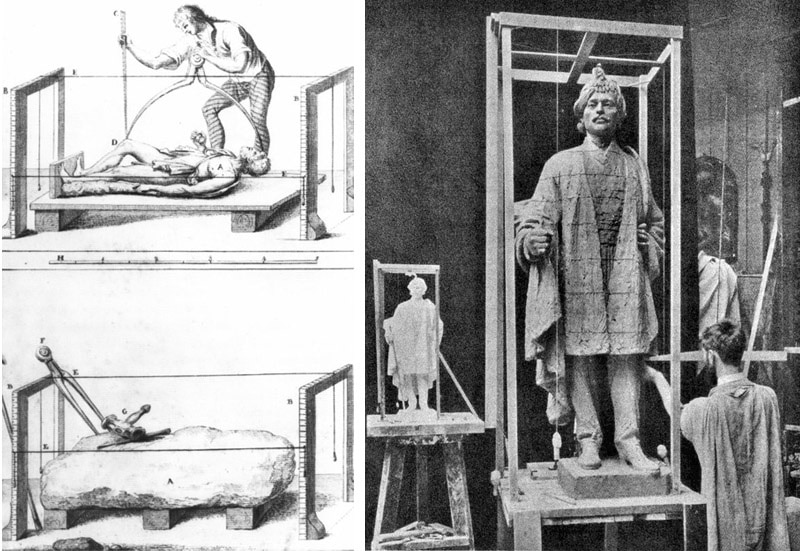

The plaster model and the marble block were therefore placed under two frames with plumb lines to indicate the points of greatest protrusion, allowing the collaborators to outline the volumes in the block. The shapes were therefore increasingly refined thanks to the so-called “pantograph method”. The distances between the nails were measured and meticulously reported on the marble with the aid of a compass, thus allowing the model to be faithfully reproduced. For this reason the plasters were never sold, but remained in the workshop to be used in future commissions, as painters already did with their cartoons.

The final phase was the one in which Canova intervened directly. It was the moment in which the sculpture was finished, bringing out the hand and the precise touch of the creator of the work.

The tools also change, from the hammer to the chisel and smaller chisels, which allow the surfaces to be treated and their different materiality to be rendered.

The fascination and appreciation of Antonio Canova’s sculptures has not always been the same. Already in the Romantic era and up to the mid-twentieth century, the artist was the victim of negative judgments. The attention to the use of correct technique and to the formal cleanliness of his works was intended as a negation of the creativity and impulsiveness that should distinguish the artistic act.

Canova was seen as a figure who suppressed the artist’s genius in favor of an aesthetic that would satisfy the prevailing taste. Emblematic of this consideration is the description that Roberto Longhi addressed to him: “Antonio Canova, the stillborn sculptor, whose heart is at the Frari, his hand at the Academy, the rest I don’t know where”.

It is important to underline how these criticisms are placed within an ideology that tended to stigmatize artists who made use of different aids and who were more attentive to the rigor of the finished work. To these figures, like Canova, artists were preferred who in their works brought out what was considered their personal interpretation of reality, first of all Caravaggio.

Recently Antonio Canova had the critical fortune he deserves, as the main exponent of the taste of a specific historical and cultural moment. Proof of this is the fame of the famous Gypsotheca of Bassano del Grappa, which we invite you to visit. In fact, the museum conserves the famous plaster casts that the sculptor kept in his Roman atelier, and which were brought to his birthplace by his half-brother, Bishop Giovanni Battista Sartori.

It is thanks to the studies of the Bassano museum that we can describe the sculptor’s techniques.

As further proof of the fortune obtained by Antonio Canova, there is also the success of the exhibition, curated by Stefano Grandesso and Fernando Mazzocca, dedicated to him at the Gallerie d’Italia in Milan. Canova / Thorvaldsen.

The birth of modern sculpture, where the sculptural production of ours and that of his Danish alter ego Bertel Thorvaldsen, also active in Rome, were masterfully compared through a huge amount of works.