Brera, the birth of the Academy

Until the seventies of the eighteenth century, the teaching of the arts was left to the workshops of individual artists, who also took care of welcoming numerous students to their studios.

These were duly trained in technique and style, which inevitably affected the personal taste of the master. If, however, there was a predominant style, based on the preference of one or the other artist on the part of the aristocratic client, there was still no school that followed a real carefully conceived program.

This important milestone was achieved thanks to the careful policy of Maria Theresa of Austria and in particular with the government of Lombardy by her son, Archduke Ferdinand of Habsburg, who remained in office until 1796, when the French.

Starting from 1773, with the acquisition by the state of the college of Brera, until then occupied by the Society of Jesus suppressed that year, the premises were used to accommodate the ambitious project of the Empress.

Maria Teresa, in fact, had conceived a real citadel of arts and science, where the teachings would no longer be promoted by religious but secular institutions, with the task of “removing the teaching of fine arts from private artisans and artists, to submit it to public surveillance and public judgment “.

In addition to the Astronomical Observatory already present under the Jesuit direction, a large public library, the Botanical Garden, the Patriotic Society (later the Lombard Institute of Sciences and Letters) and, in 1776, the famous Brera Academy of Fine Arts were added.

The latter in particular found great support from the plenipotentiary minister Firmian and Archduke Ferdinand, aware of the importance of forming a new generation of artists who could also relaunch the cultural, and therefore political, image of the duchy.

Right from the start, in fact, the Academy became a prestigious school where the most important and sought-after artists of the time were trained, under the guidance of equally well-known teachers.

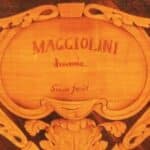

Among these, one of the most famous, was Giocondo Albertolli, named “Master of the Ornato School” from 1776, a position he held until 1812. Among the main exponents of Milanese Neoclassicism, Albertolli boasted many collaborations, among which the most known is certainly the one with the carver Giuseppe Maggiolini.

His role as teacher at the most prestigious Milanese Academy certainly contributed to the spread of his style and of his decorative motifs, which are actually found in the vast production of the time.

It was also understood the need to equip the school with its own collection that would serve as a model for the students.

Thanks to the intuition and will of Carlo Bianconi, secretary of the Academy and a collector himself, the collection of plaster casts, engravings and drawings to be used for the training of artists was started. This first collection was the basis of the current huge collection of the Pinacoteca, enriched thanks to the works coming from the Teresian suppressions but above all, a few years later, thanks to the works received following the Napoleonic requisitions.

The desire to characterize itself as an innovative and avant-garde institution was evident from the beginning, also with the design of the new architecture that would house the Academy and the future Art Gallery.

Giuseppe Piermarini, Inspector General of state factories in Lombardy, was in charge of the renovation. In particular, he was responsible for the construction of the emblematic neoclassical portal that characterizes the facade on Via Brera, still the main access to the building today. In addition to the building renovation, Piermarini was fundamental for the life of the newborn Academy in holding the chair of architecture, starting from 1776.

Another fundamental year was 1803, when important changes were made by the secretary Giuseppe Bossi.

He carried on what had already begun by Bianconi, believing it was now necessary to equip the Academic Institute with its own Gallery, which would be open, both to the public and to students, three years later. Bossi’s merit, however, was above all that of transforming and improving the entire teaching system. The teachings were implemented and divided as follows: Architecture, Painting, Sculpture, Ornament, Engraving, Perspective, Artistic Anatomy and Figure Elements. Their coordination was submitted to an academic council, made up of thirty members.

Furthermore, Bossi, following the Parisian example, widely promoted the annual competitions and exhibitions, in which the students of the school were called to participate. These exhibitions had in fact the task of presenting the very high artistic production emerging from the Academy, characterizing themselves as exemplary exhibitions that showed the artistic updates of which the new institution was the bearer.

If originally the events of the Pinacoteca and the Academy were closely linked, the key moment was 1882, the year in which the two institutions were separated.

The museum, now autonomous, was rearranged on a project by the director Giuseppe Bertini.

Even today both the Academy and the Pinacoteca are characterized as two prestigious institutions, one for the training of future artists, opening up to new teachings, feasible thanks to the use of new technologies and artistic forms, the other for both the considerable and a complete collection that it houses but also for the desire to modernize the museum, revealed by recent works and those to be completed.

An important figure in the history of the Brera Academy was Count Barbiano di Belgiojoso, President from 1860 to 1876.

He himself, even before his appointment to the prestigious position, dabbled in painting, presenting his works at the exhibitions organized by the Academy. Among his works, in our possession (visible here), Christopher Columbus, departing from the port of Palos, recommends his children to Father Giovanni Perez, a copy of the famous painting by Pelagio Palagi now preserved in the Pinacoteca di Brera.