The ceroplasty

Ceroplasty is an ancient wax working technique, already attested in ancient Egypt. Used for a long time in funerary, devotional and portraiture fields, it has been used since ancient times for various uses, but, due to the great perishable nature of the material, only rare specimens have come down to us.

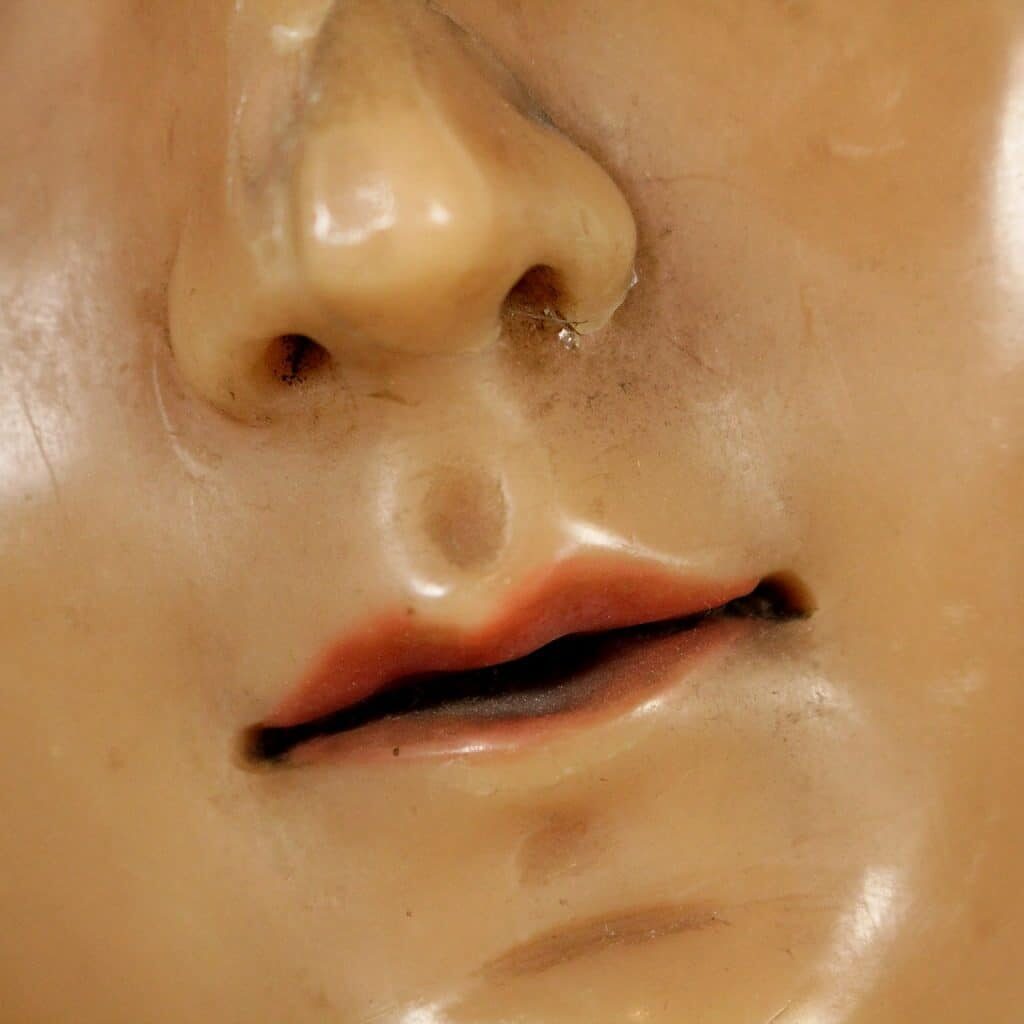

In fact, beeswax has a relatively low melting point and therefore lends itself to being easily molded: this allows the artist to make corrections, additions or oblations to the model at any stage of processing. Thanks to its ductility and the possibility of continuously varying its consistency, the wax can be worked according to traditional sculptural techniques: modeling, casting in molds and carving.

The wax was prepared with additives, such as tallow (animal fat) and turpentine, which gave the mixture greater plasticity. The addition of pitch or resin, on the other hand, ensured greater hardness. Once the mixture was prepared, we proceeded with the coloring, obtained by adding – in the molten state – powdered pigments, or with gilding and / or silvering. The wax could then be associated with other material elements, used both as supports and as ornaments: there were frequent applications of fabrics and inclusions such as glass, pearls, hair, gold threads, ornaments with precious metals, corals, etc.

In addition to sculptors, goldsmiths and medalists also used wax to create models of their creations.

Thus Benvenuto Cellini, sculptor-goldsmith-artist, described the processing of wax plastics:

“This wax is made like this: take pure white wax and mix it with half of well ground white lead with a little light turpentine; this is more or less, depending on what season the man is found, because, being of winter , you can give it more turpentine than half you are. Then with some wooden spindles this wax is worked into a round of stone or bone or black glass. “

B. Cellini – The treatises of goldsmithing and sculpture

The peculiarities of wax – easy to find, cheapness, ductility, malleability, ease of processing – have meant that it was used over time in various fields: making tools, amulets, ornaments, or as a base for metal castings of sculptures at all. tondo, jewels and coins, or as a draft of sculptural works, or for scientific purposes, without obviously forgetting the devotional repertoire and portraiture.

The working of the modeling took place with the aid of particular tools, not far from those used for working with clay, such as bone, iron or wooden sticks.

The Egyptians used wax to create small figures of a magical-religious nature made using the colombino

technique or more complex processes (such as the overlapping of layers of wax then carved or the covering of a core of vegetable fibers through layers of wax ), up to the creation of products obtained by casting in molds.

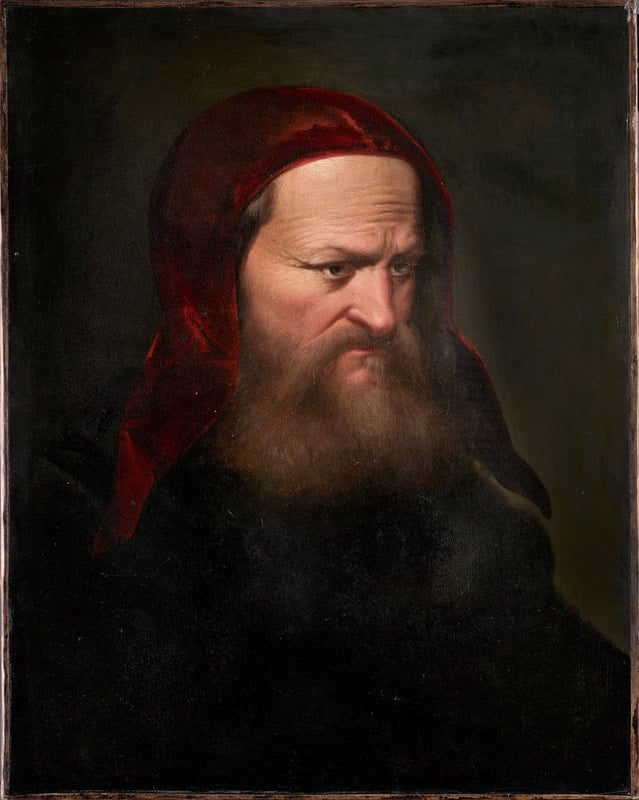

It is towards the sixteenth century that wax-plastic surgery reaches its peak as a real sculptural material, both in the portraiture and in the votive-funerary sphere.

In Florence, between 1200 and 1500, a real industry of wax votive offerings flourished. Local history tells that in the thirteenth century an image of a Madonna who was reputed to be miraculous was hung on a column in Orsammichele; the faithful came on pilgrimage from all parts of Tuscany bringing ex-votos in wax, “bóti” as they were called, to the venerated image of “Our Woman”.

They accumulated by the thousands, but they were all destroyed and even stoked the flames when the Black Guelphs set fire to the Orsammichele loggia, the oratory of Our Lady and the Cavalcanti houses on 10 June 1304.

Soon the Church with the Oratory was rebuilt and the cult of votive offerings in wax resumed. In the meantime, however, the fame of the miracles of another Madonna had already spread to the church of S.S. Annunziata, and popular veneration poured into this second image. The votive offerings, the “boti”, which flowed into it were of all kinds, representing members or parts of them, portraits, objects and even animals.

Not to be forgotten is the use of wax aimed at creating preliminary sketches of major works.

Filarete, already in the mid-1400s, in his Treatise, provides some information on the use of wax for the creation of small-scale models of future works:

“Carving when drawing is understood well is an easy thing: a little practice is needed, if you want to carve with wax; because anyone who wants to make bronze is a job to do before wax, and wax wants to be made black and soft with turpentine and sevo, and then crushed charcoal to make it black, although whoever wanted it could be colored in any color: white, red, green, blue, yellow, and in short, it can be made of any color “.

Numerous examples of wax sketches have also been preserved by famous artists: among the many worthy of note is that of Michelangelo’s David (Florence, Galleria Buonarroti), that of the Perseus by Cellini (Florence, National Museum), that of Hercules and Caco of Bandinelli (Berlin, Kaiser Friedrich Museum), those of Ferdinando I de ‘Medici (Berlin, Kaiser Friedrich Museum), two reliefs of the Passion by Giambologna (London, Victoria and Albert Museum)

Towards the end of the 1600s the first anatomical models in wax appeared: the rediscovery of the human body, the studies of cadavers and the interest in anatomy led to the use of wax also in the medical-scientific field.

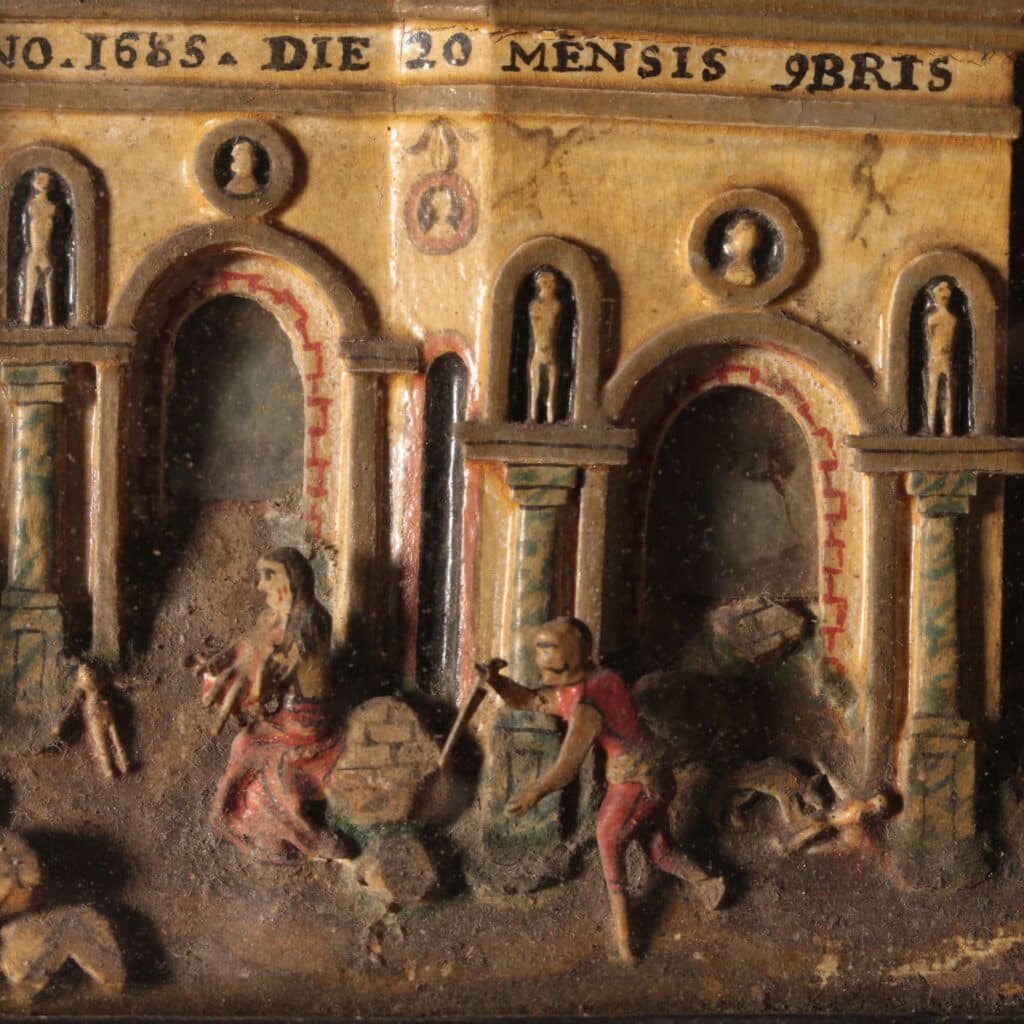

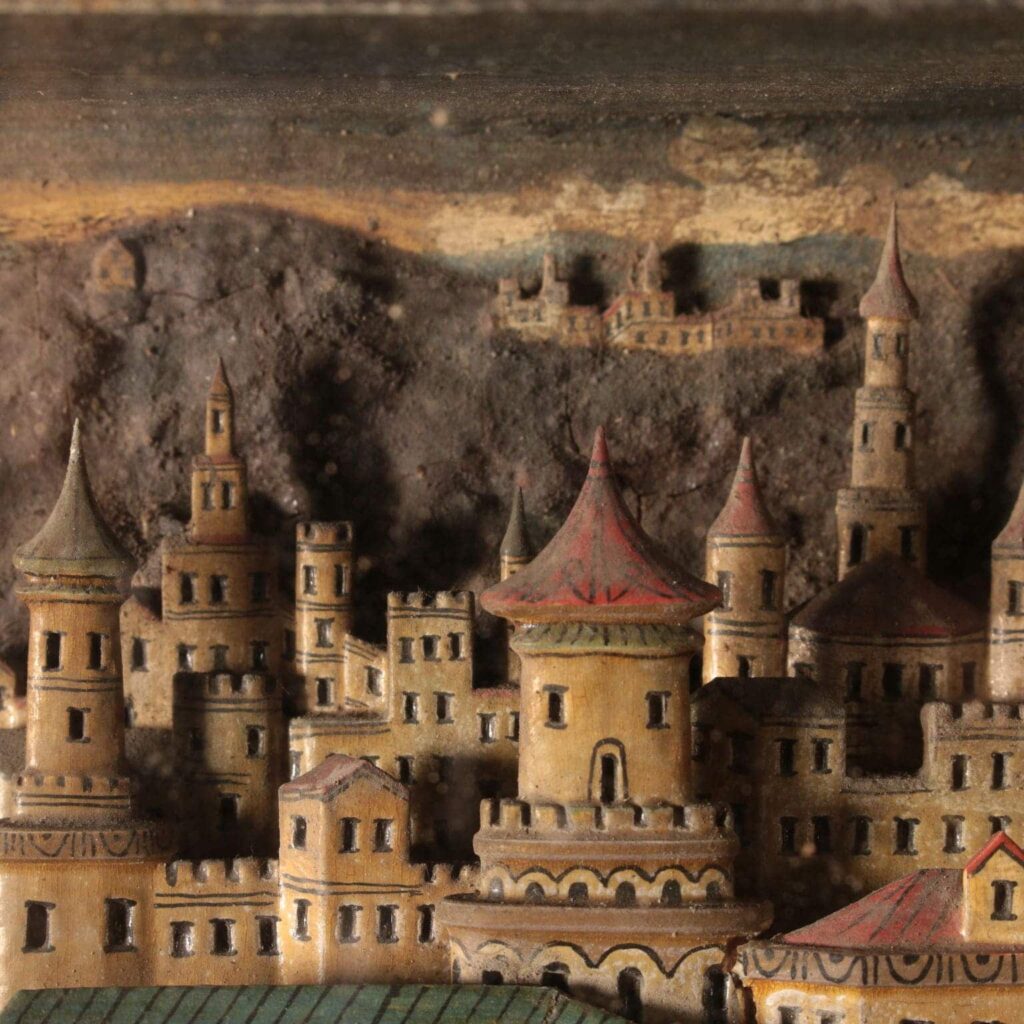

However, wax plastics proper is an art form practiced with the intention of creating a well-defined aesthetic object, carefully adorned and decorated, finished in the smallest detail. The highest forms of this art are to be found in the production of Neapolitan and Sicilian plastic bambinelli and tableau.