The Portrait in Italian painting

The will to pass on one’s image to posterity has always been present in man.

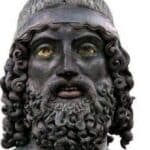

Since Roman antiquity, emperors were represented in profile on coins. Although idealized, these representations were quite faithful, and their face was certainly known by their subjects. The intention of spreading their own image was such that the emperors, as soon as they ascended the throne, took

care to refund the coins that portrayed their predecessor, to replace them with their own.

Over the following centuries, sovereigns and aristocrats from all over Europe were portrayed by the greatest artists. The real diffusion of the portrait took place in the Renaissance period, by virtue of the new humanist conception which saw the centrality of man as an individual.

Famous portraits of Italian authors placed in the Uffizi Galleries.

Famous is the double portrait, which takes up the tradition of Roman numismatics, of Federico da Montefeltro and his wife Battista Sforza, the work of Piero della Francesca and today in the Uffizi Galleries. The artist was able to grasp the military austerity and the great charisma of the Duke of Urbino, who was deliberately represented in profile to hide the lack of an eye, lost during a joust.

If for a long time the portrait remained the prerogative of the nobility, soon the rising bourgeoisie also began to commission their own portraits to artists. Agnolo Doni, a wealthy Florentine merchant, commissioned the portrait of him and that of his wife, Maddalena Strozzi, from Raphael. On this occasion the artist showed a great introspective capacity and psychological rendering. The acuteness of the portrayed can be guessed from the look, while the contemptuous posture reveals his high social position.

Particular attention must be paid to the fortune that the portrait line had in Lombardy, starting from the sixteenth and up to the eighteenth century.

The one who made a strong contribution to the development of the portrait was Giovan Battista Moroni, an artist active between Albino, a town in the Val Seriana and Bergamo, but trained in Brescia under the guidance of Moretto. Moroni was an artist much appreciated by local clients, both noble and bourgeois. His portraits di lui, many of which can be admired in room 17 of the Carrara Academy, are in fact characterized by a very particular attention to the rendering of his physiognomy and clothes di lui. In particular, those belonging to the earliest years, such as the Portrait of Isotta Brembati Grumelli, are characterized by a typically Nordic objective description that reveals the knowledge of Flemish art, certainly observed during his stay in Brescia.

But the reason that made it more appreciated by its clients was the great human and moral capacity of the characters represented, especially the high craftsmen belonging to the bourgeoisie. The palette used by the artist in the most advanced phase of his career is instead made up of a flatter chromatic range and earthy colors. The artist’s attention is now entirely focused on psychological introspection. The attention is focused exclusively on the faces and attitudes, while the fabrics are sober. The portrayed wants to show himself and be remembered not only for his own wealth, but for the example of moral dignity of which he is the bearer.

From Giovan Battista Moroni to the “Pitocchetto”.

Certainly influenced by Moroni’s portraiture was Giacomo Ceruti, also known as the “Pitocchetto”. He too paid particular attention to the psychological representation of those he represented. His best-known production, the one that earned him the name by which he is known today, sees the humanity of the poorest, beggars, peasants, the so-called “beggars”, as protagonist. Ceruti was able, with his art, to give the last a new dignity.

Their social condition is not denied, but at the same time it becomes the bearer of a new and high spiritual value. the “beggars” are depicted in the performance of their daily activities, caught as in a quick snapshot that portrays them and gives them new pride.

Thanks to the ability to empathize, Ceruti becomes the bearer of that Lombard tradition “painting of reality”. Even the last ones can play an important role in the history of art, no longer destined only for the rich and powerful.

Although this is the trend for which Ceruti is best known, the artist was also active for the aristocracy. Appreciated for his skills as a portraitist and the ability to make a simple portrait a real declaration of intent, there were many nobles who commissioned portraits from him. The painter became the official portraitist of the small Lombard aristocracy, also elevated and awarded a new value, like the great European princes.

An example of this is our Portrait of Giulio Orsini, made by 1755, as a model for the realization, that same year, of the equestrian portrait of the portrayed today in the Koelliker collection.