Rococo

Rococo was born in France in the first half of the eighteenth century, as a natural evolution of the prevailing style in the previous century: the Baroque.

The name derives from the French “rocaille”, a term used to indicate a specific type of decoration with the use of stones and shells.

This style developed mainly in the countries beyond the Alps. In Italy it developed mainly in the northern centers (Turin, Milan, Venice) and in the port cities (Genoa, Naples, Palermo), where contacts with France were favored. In the rest of the peninsula, however, the Baroque taste remained firmly established, which had had Rome as its epicenter. For this reason, all the regions that were influenced by the Papal State arrived late with a style called Barocchetto, mostly a very light Baroque, to then quickly pass to Neoclassicism.

From the Baroque the Rococò directly inherited the love for phytomorphic decorations, whose ancestor is to be found in the mannerist grotesques.

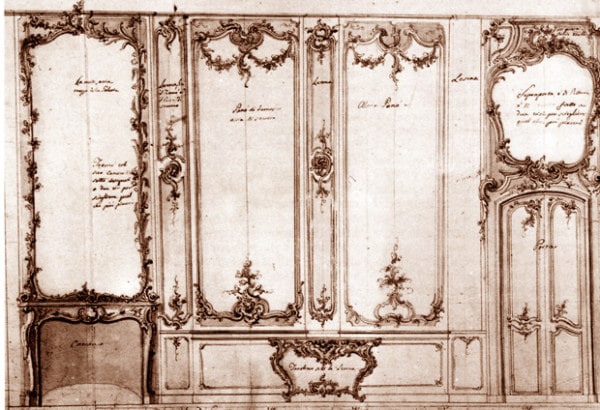

Between the end of the seventeenth and the beginning of the eighteenth century the technical discovery of making larger mirror plates (the mirrors had an illuminating function, they reflected by expanding the light of the sun or of the lights, in fact in the inventories they are often called “lights”) brings a big change in the furniture, which transforms the brightness of the houses and the composition of the boiserie. Thanks to this, halls are set up in the palaces for parties and balls, where large mirrors are adorned with refined gilded stuccoes, which elegantly enliven the architecture and reflect light with a precious gold-colored reverberation.

Rather than in actual architectural forms, Rococo found ample use, as we have seen, in decorations. The sinuous but refined lines found great application in furnishings and small objects, especially ceramics and bronzes, which best suited these shapes.

The structure of the furniture such as wardrobes, sideboards and trumeau moves, with shaped and curvilinear profiles, making the silhouette graceful and elegant and covering the furniture with precious exotic woods, such as rosewood. Particularly relevant is the comparison between the Baroque parade tables and those expressing the Rococò taste. The former are characterized by a real sculptural apparatus that replaces the base, surmounted by a heavy marble slab that forms the top. The eighteenth-century consoles are instead built with thinner shapes and have a decoration that does not negate the supporting structure. The legs also get rid of the central crosses, they bend and the decorative carving takes up vegetal or natural motifs such as shells, in a less theatrical way than in pure Roman Baroque, but with a purely decorative and charming purpose.

Sometimes the decoration is completely removed, leaving the structure with its wavy shapes on display. Even the tops in some cases are modified, no longer in marble but in wood, often finely inlaid with elegant arabesques in line with the Rococo style.

Rococò is a style characterized by a direct derivation of the Baroque style, a natural evolution in the light of the profound changes that characterized the early eighteenth century.

Already before the middle of the century, however, some writers and philosophers, tired of the debauchery in which the aristocracy lives, driven by some archaeological discoveries, will lay the foundations of the Enlightenment that will lead to a great social and arts change.