Giuseppe Maggiolini

Born in Parabiago on 13 November 1738, Giuseppe Maggiolini was soon orphaned and was welcomed by the Cistercian monks at the monastery of Sant’Ambrogio della Vittoria. Here he attended the carpentry workshop and learned the ancient practice of wooden inlay.

In these same years he received the precepts of the learned priest Antonio Maria Coldiroli (1728-1793), at the time a teacher at the noble Collegio Cavalleri.

He gives the young Maggiolini lessons in drawing and architecture from books and treatises of the Italian sixteenth century.

He gives the young Maggiolini lessons in drawing and architecture from books and treatises of the Italian sixteenth century.Not yet twenty years old Giuseppe Maggiolini is already active as a carpenter with his own workshop directly overlooking the main square of Parabiago.

In 1758 his first son Carlo Francesco (1758-1834) was born, who will work alongside him throughout his life.

In its first years of activity, Maggiolini made fully Rocaille furniture, characterized by wavy and nervous lines.

A pair of walnut game tables and ebonized frames signed by Maggiolini himself and dated 1758, now in a private collection, testify to this.

A few years later is the commode à pieds elevée preserved in the Civic Collections of Milan.

With its elegant proportions, the commode is entirely covered with large walnut briar sheets that enhance the slender and graceful rocaille decoration, finely shaded and profiled boxwood inlay. These first works are linked by the same inspiring models: the tables by Franz-Xavier Habermann published starting from 1756 by the publisher Hertel in Augsburg which represent furniture designed according to the most extreme Rocaille forms.

The young Maggiolini is thus fully capable of declining Lombard furniture according to the most up-to-date European taste.

The notoriety of the young and promising cabinetmaker soon reached the archducal Milan, probably thanks to the Marquis Giovanni Battista Moriggia, a nobleman with properties in the Parabiago di Maggiolini and owner of the homonymous Milanese palace.

The good relations at court are worth to Moriggia the organization of the celebrations for the wedding between Archduke Ferdinando and Maria Beatrice d’Este, celebrated in 1771.

It was in the Milan of those years that Maggiolini met and formed a fruitful partnership with the decorator and plasterer Agostiono Gerli (1744-1821). After spending six years in the atelier of Honoré Guibert (1720-1791) with whom he worked on the decorations of the Petit Trianon by Versaille, Gerli returned to Milan where in 1769 he inaugurated a decoration and furniture workshop with his brothers Giuseppe and Carlo. Thus a taste updated according to French fashion arrives in Milan.

In his workshop in Parabiago Maggiolini makes furniture designed by Gerli, according to the shapes of the Parisian Rocaille, characterized by rare exotic woods, dyed and shaded, polychrome inlays, precious gilded and finely chiseled bronzes. This production includes two pieces of furniture preserved in the Art Collections of the Municipality of Milan: a small work table and a commode with chinoiserie taken from the prints of Antoine Watteau (1684-1721) and embellished with gilded bronzes with chinoiserie, masks and snakes inspired by the Nouvelle Iconologie by Jean-Charles Delafosse (1734-1791).

Still on a project by Agostino Gerli, in 1773 Giuseppe Maggiolini created a desk commissioned by Archduke Ferdinand, sent as a gift to his mother, the Empress Maria Theresa of Austria. Preserved at the Möbel Museum in Vienna, the desk bears inlay, on the top and sides, chinoiserie invented by Giuseppe Levati (1739-1828).

However, taste and fashion changed abruptly in the Europe of those years. The new imperial directives of Maria Teresa arrive in Milan, which require architecture to recover classicism. The two key figures, vehicle of the new style, are Giuseppe Piermarini (1734-1808), appointed Royal Imperial Architect in 1769, and the Ticino-born Giocondo Albertolli (1742-1839) called to Milan in 1774 to take care of the decorations of the new court palace. . Consequently, even the furnishings must soon adapt to the dictates of the new classicism.

Giuseppe Maggiolini was awarded by the Archduke Ferdinand the Inlayer’s patent of their Royal Highnesses, thus becoming the supplier of the court palaces.

The cabinetmaker from Parabiago makes furniture designed as precious donations on commission from the archduke: a commode is sent to Modena to his father-in-law Ercole III d’Este, a writing desk in Naples for his sister Maria Carolina, a secrétaire in Parma to the other sister Maria Amalia, a tripod is sent to St. Petersburg as a gift to the Tsar and an inlaid painting in Warsaw for the King of Poland Augusto Poniatowski.

The years to come saw the great city families update their villas and palaces according to the new taste guidelines. Having now become a status symbol, the furnishings made by the cabinetmaker from Parabiago are increasingly in demand.

In 1777 the banker Antonio Greppi commissioned Giuseppe Maggiolini for a pair of commodes. These two imposing pieces of furniture today unpaired, one in the Milanese Civic collections, the other in a private collection, are made to a design by Agostino Gerli, perhaps the creator of the ingenious mechanism with a central door which, once raised, re-enters the body of the mobile making available the two internal drawers. On these large façade tableaux, as on the sides, figurative allegories of virtue based on

a design by the young Andrea Appiani (1754-1817) are translated into inlay by the now skilled cabinetmaker from Parabiago. The commode now in the public collection is undoubtedly one of Maggiolini’s most representative creations, already defined by Alvar Gonzàlez-Palacios as a “monumental work, […] which has always been considered one of the milestones of Italian neoclassical cabinet-making. And perhaps European “.

Another important order came in 1784 from the Marquis of Genoa Domenico Serra.

Renovated his palace according to the most up-to-date French taste on a project by Charles de Wailly (1730-1798), the marquis commissioned an important furniture to Giuseppe Maggiolini. It is a commode covered on the entire surface with very fine inlays and embellished with gilded bronzes. It is always Agostino Gerli who defines the layout, while Maggiolini entrusts himself once again to Giuseppe Levati for the decorative party. Of the important piece of furniture, which was lost during the bombing that destroyed the entire building in 1942, the preparatory cartoon and a photograph taken in 1874 are preserved.

For the wedding celebrated in 1789 between Lodovico Busca and Luigia Serbelloni, Giuseppe Maggiolini made two monumental commodes, already defined by Giuseppe Beretti as “the masterpiece of his entire career”.

The project, according to the taste of Louis XVI, belongs to Giocondo Albertolli, the inlays with mythological figures inspired by the theme of love and games of cherubs are instead executed on a design by Andrea Appiani. The large frontal tableaux, the female caryatids in gilded wood and the original sixteenth-century bronze hippogriffs suggest a reinterpretation of the Renaissance chest in a neoclassical key.

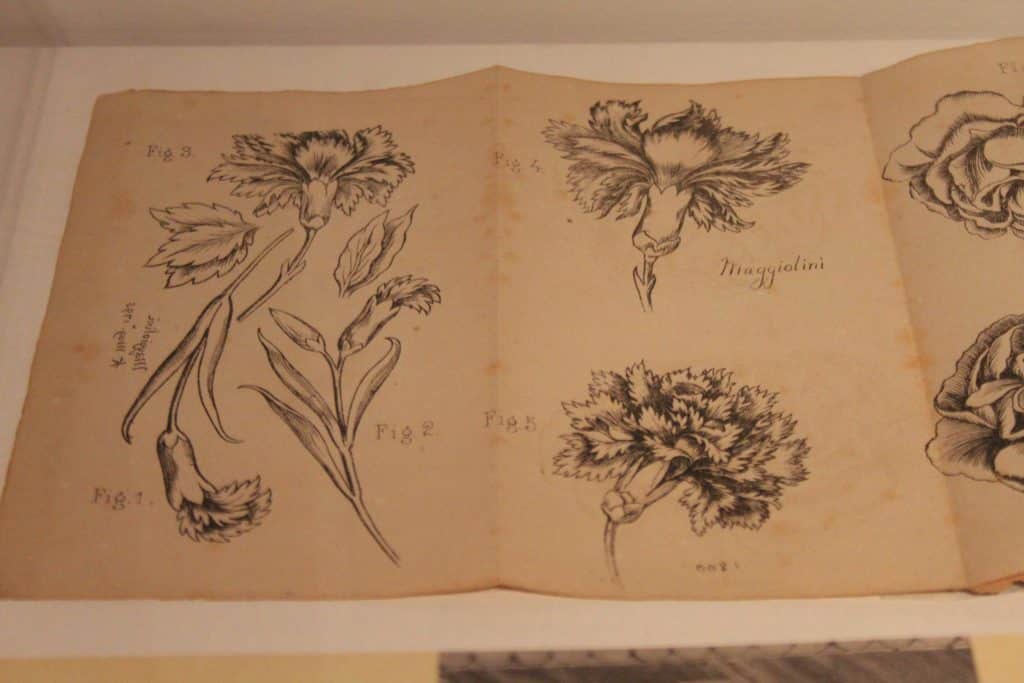

These were happy years for the Parabiago workshop which dismisses high quality furnishings. Tables, secretaires, commodes, desks, small caskets, all furniture designed with drawers and secrets with ingenious mechanisms. Gradually the gilded bronzes disappear to give way to weaving of woods shaded by burnishing in the scorching sand. The finely inlaid figurative repertoires are increasingly elegant racemes, bouquets of flowers and whims from antiquity: tripods, cippi, vases and obelisks, inventions derived from the d’aprés that Giuseppe Levati performs for Maggiolini of some tables of The Antiquities of Herculaneum on display , published in Naples between 1753 and 1792. The important orders received by the most prominent families of the time, the Borromeo, the Litta, the Trivulzio, the Andreani, the Carpani, the Visconti di Modrone, are becoming more and more frequent.

This prosperous season, however, ended on 10 May 1796. Napoleon Bonaparte’s army won the battle of Lodi, and Archduke Ferdinando, the most important client of Giuseppe Maggiolini, was forced to leave Milan.

The court palaces are soon looted, furniture and furnishings sold at auction to finance the French army. The most important creations of the cabinetmaker from Parabiago are thus dispersed, largely forever lost.

With the escape of the great city families, the years to come were marked by enormous difficulties for the workshop of Giuseppe Maggiolini. To see a recovery, one must wait for the establishment of the court and the coronation of Napoleon Bonaparte, King of Italy, celebrated on May 26, 1805 in the Milan Cathedral. The imperial palaces must be furnished from scratch, after the looting of 1796. Giuseppe Maggiolini is so called to make furniture according to the new taste of the court: no more old regim furniture with delicate chromatic transitions obtained from polychrome woods, no more nostalgia for the ancient but rather furniture with hard and military profiles, decorated with floral garland inlays on mahogany backgrounds and embellished with sparkling gilded bronzes.

It is no longer the aristocratic families of the past who commissioned furnishings from the Parabiago workshop, but officials of the Napoleonic government or bourgeois citizens such as lawyers and doctors. Thus began a vast production of workshop, almost serial, design ante litteram, of commodes, tables, secretaires, all executed with small variations of inlays,

always repeated and modulated according to the spending possibilities of the clients. Giuseppe Maggiolini still relies on Giuseppe Levati, now professor of Perspective at the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts in Brera, on Carlo Cantaluppi or Girolamo Mantelli only for the creation of furniture for distinguished clients.

However, the production of inlaid furniture began to thin out from 1810, until it finally ceased in 1814, when Giuseppe Maggiolini died at the age of seventy-six in his Parabiago.

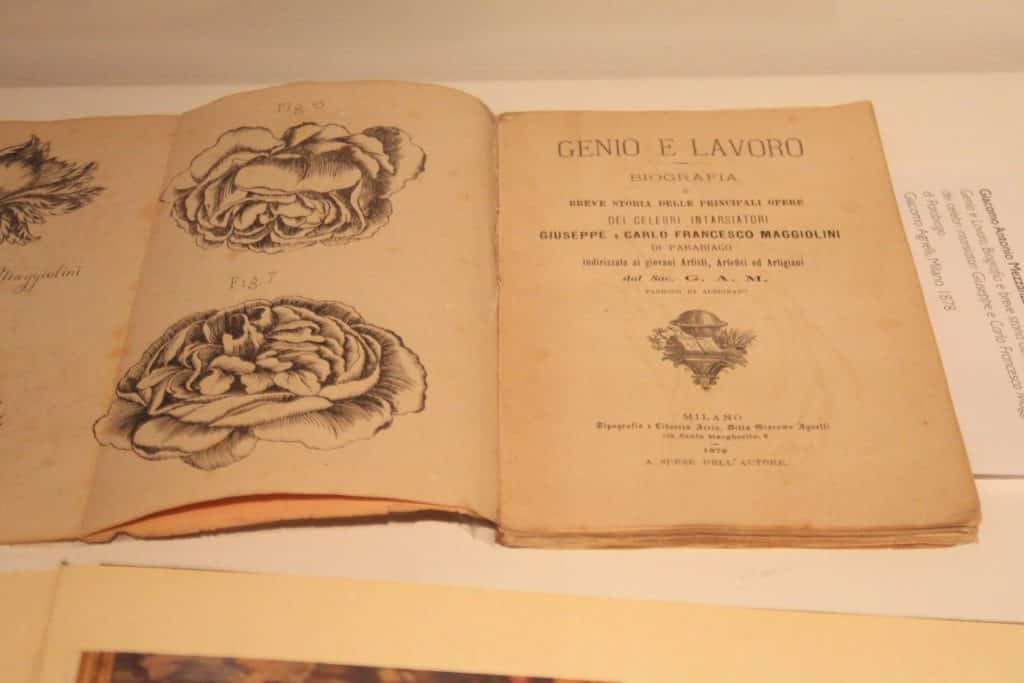

The workshop continued its cabinet-making work until 1834, directed by his son Carlo Francesco, flanked by his collaborator Cherubino Mezzanzanica. What is saved from the glorious manufacture of Parabiago is the archive of drawings made up of over two thousand sheets used by Giuseppe Maggiolini for the execution of furnishings and inlays throughout his brilliant career. The entire corpus of drawings and projects passes into the hands of the son of Cherubino Mezzanzanica, that Giacomo Antonio (1826-1880), then parish priest of Albignano, who dedicates the first history of workshop, published in Milan in 1878. A few years later the precious archive appears on the antiques market, at the merchant Pietro Grandi with a shop in Corso Venezia.