Giocondo Albertolli

Giocondo Albertolli was one of the protagonists of the neoclassical style, an exponent of that culture of light that characterized the arts at the turn of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Born in the district of Lugano, in Bedano, on 24 July 1742, he made his first studies in Aosta, where his father Francesco Saverio worked as an architect. From a very young age he was initiated into an artistic career.

In 1753, when he was just eleven, he was in fact sent to Parma at his uncle’s shop. The first approach to Giocondo’s art must probably have been characterized by the typical activities of the Ticino plasterers’ workshops: drawing, modeling and making the stuccos. In 1768 he was also indicated as a pupil of Benigno Bossi, another Parma artist active in various construction sites in the city.

Parallel to the artisan training in various workshops, ours also followed the artistic one at the Academy of Fine Arts in Parma, also participating in the annual academic competitions and winning in two of these.

In those years the chair of architecture was held by the famous architect Ennemond Alexandre Petitot, to whom we owe the decorations for the most important and grandiose works for the prestigious commissions of Parma.

Although Albertolli himself, in his memoirs, does not remember any direct contact with the French architect, one can well understand how he must necessarily have been influenced by him, probably having followed his academic courses and having seen the works he directed in the Parma construction sites.

From the very beginning, Albertolli’s great skill as an ornatist emerged, now able, in his early twenties, to create stuccos independently.

At the age of twenty-seven he was in fact indicated as a professional plasterer. In 1770 he carried out the decoration of some of the interiors of the palace built by the Marquis Scipione Grillo of Monterotondo (today Palazzo Marchi). Here the stylistic characteristics emerged that will be characterized as constant in our career. Giocondo Albertolli proved to be able to wisely combine what he learned during the years of his formation, in particular the typical taste of the Rococò quadraturists and ornamental elements of Louis XVI style derived from the work of Petitot. Albertolli did not simply take up these elements, but reworked them according to his own sensitivity.

1771 was a fundamental year for Albertolli, during which he was consecrated among that group of artists whose services were disputed among the main courts of the peninsula.

He was in fact called by Pietro Leopoldo to work at his Tuscan court. In particular, ours was summoned as head of the Parma plasterers, as the creator of some of the furnishings and decorations desired by the Grand Duke for his home in Poggio Imperiale. Albertolli’s work at the Florentine court was certainly appreciated, as evidenced by the artist’s call to Milan in 1774. The city was in fact subject to the government of Ferdinando, brother of Pietro Leopoldo, who certainly had suggested hiring the Ticino artist.

Albertolli therefore embodied that taste, expression of wealth and elegance so dear to the Habsburg family. His intervention was required in the construction sites of the large representative palaces that the two archdukes were having built in the cities subject to their control.

The Milanese convocation took place by the hand of another great architect, Giuseppe Piermarini. At the head of the large construction site for the Palazzo Arciducale, Piermarini was looking for a

plasterer who was up-to-date on the new way of decorating and, as already mentioned, the name of Albertolli was probably suggested by the two brothers of the Habsburg family. If for the first years Giocondo Albertolli continued to move between Florence and Milan, he settled permanently in the Lombard capital starting from August 1775. In the following years he continued the work on the building and obtained another prestigious assignment.

In fact, from 1776 (and until 1812) he became a teacher at the newly created Academy of Fine Arts in Brera, where he held the chair of ornamentation. His course turned out to be among the most appreciated and followed, as the Firmian plenipotentiary himself recalls. Albertolli must certainly have been proud to cover this prestigious role, as also demonstrated by having declined in 1781, the invitation to teach at the Academy of Parma, where he himself had trained.

Certainly Albertolli’s appreciation grew over the years, allowing him to access the main Milanese construction sites and meet the most important artists of the time.

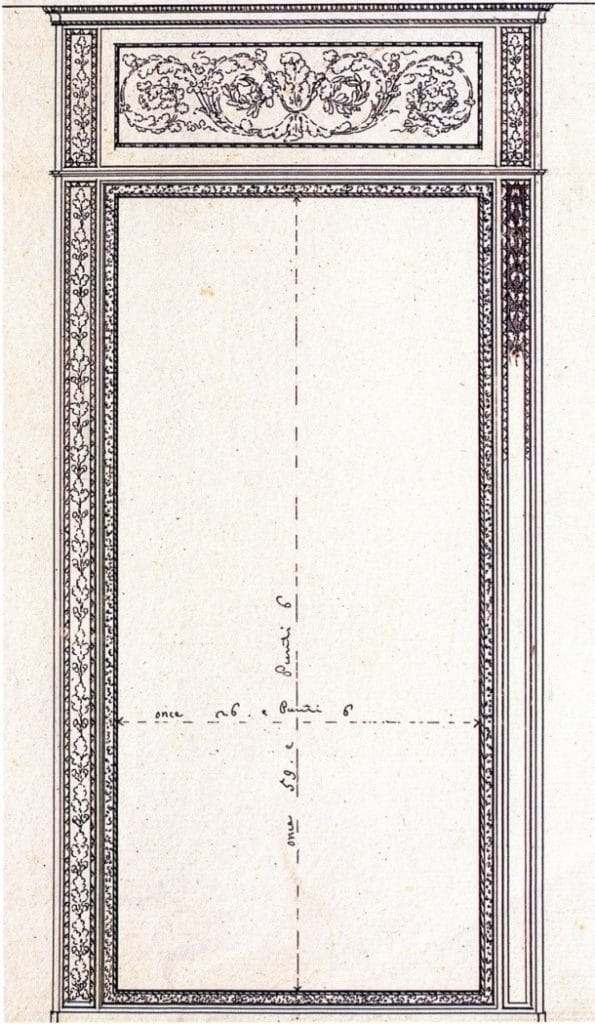

In particular, ours had the intuition to understand the lack of a real repertoire with the ornamental motifs typical of the New Manner, from which decorators and architects could draw if necessary. Probably also thanks to his experience as a teacher, in the 1880s, Albertolli had his first collection of ornamental models printed: Different ornaments invented, designed and executed by Giocondo Albertolli.

From this work, followed by others, it emerges that the artist was able to recover decorative motifs with an archaeological flavor which, decontextualized from their original use and filtered through the use that Renaissance Florence made of them, become the true protagonists of ‘ornament.

The client and the spectators find themselves admiring well-known models of classical antiquity, now placed at the center of the representation. Giocondo Albertolli’s extreme sensitivity is shown both in the ability to combine these heterogeneous elements, and in the colors: delicate halftones in the backgrounds alternate with stuccoes left in plaster and gilded borders.

Unfortunately, of all the rooms of the Archducal Palace, decorated under the direction of Albertolli, only what was intended to be the audience hall has survived. Unfortunately all the others were destroyed by the allied bombing in 1943. Even the furniture that ours designed was lost; of it only a couple of console tables remain today at the Royal Palace and little else.

The appreciation of the work carried out by Albertolli was such that once the construction of the Archducal Palace was completed, he was called to take care of the decorations of the villa in Monza. Also in these years he was also active in two other Milanese construction sites led by Giuseppe Piermarini: Palazzo Belgiojoso and Palazzo Greppi.

Among his other most famous contributions is the Villa Melzi d’Eril in Bellagio, on Lake Como.

He died in Milan on November 15, 1839, after having trained numerous students and having worked with various artists, who for a long time still used his rich catalog of models as a reference for their production